Content from RとRStudio入門

Last updated on 2025-11-11 | Edit this page

Overview

Questions

- RStudio内でどのように操作するのか?

- Rとの対話方法は?

- 環境をどのように管理するのか?

- パッケージをどのようにインストールするのか?

Objectives

- RStudioの各ペインの目的と使用方法を説明する

- RStudio内のボタンやオプションの場所を見つける

- 変数を定義する

- データを変数に代入する

- インタラクティブなRセッションでワークスペースを管理する

- 数学および比較演算子を使用する

- 関数を呼び出す

- パッケージを管理する

ワークショップを始める前に

ワークショップで使用する一部のパッケージが正しくインストールされない(または全くインストールされない)場合があるため、お使いのマシンにRとRStudioの最新バージョンがインストールされていることを確認してください。

なぜRとRStudioを使うのか?

Software CarpentryワークショップのRセクションへようこそ!

科学は多段階のプロセスです。 実験を設計してデータを収集した後、本当の楽しみは分析から始まります!このレッスンでは、R言語の基本を教えるとともに、科学プロジェクトのためのコードを整理するベストプラクティスを学び、作業をより簡単にする方法を紹介します。

データを分析するためにMicrosoft ExcelやGoogleスプレッドシートを使用することもできますが、これらのツールは柔軟性やアクセス性に限界があります。さらに、元データの変更や探索の手順を共有することが難しいため、これは「再現可能な」研究にとって重要なポイントです(再現可能な研究についてはこちら)。

したがって、このレッスンでは、RとRStudioを使用してデータの探索を始める方法を学びます。RプログラムはWindows、Mac、Linuxオペレーティングシステムで利用可能で、上記のリンクから無料でダウンロードできます。Rを実行するために必要なのはRプログラムだけです。

しかし、Rをより使いやすくするために、同じくダウンロードしたRStudioというプログラムを使用します。RStudioは無料でオープンソースの統合開発環境(IDE)で、組み込みエディタを提供し、すべてのプラットフォームで動作します(サーバー上でも利用可能)。バージョン管理やプロジェクト管理との統合など、多くの利点があります。

概要

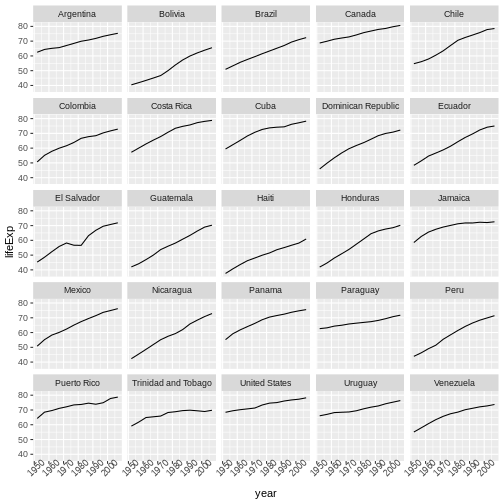

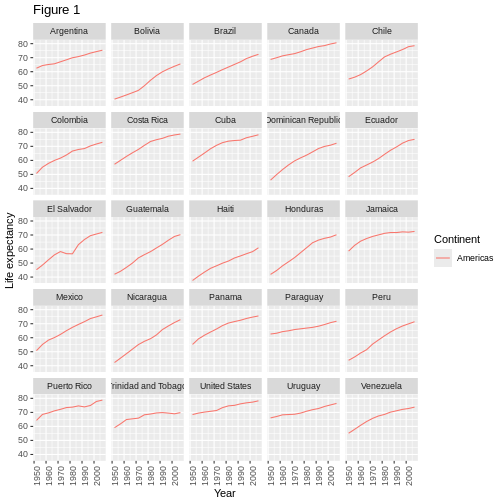

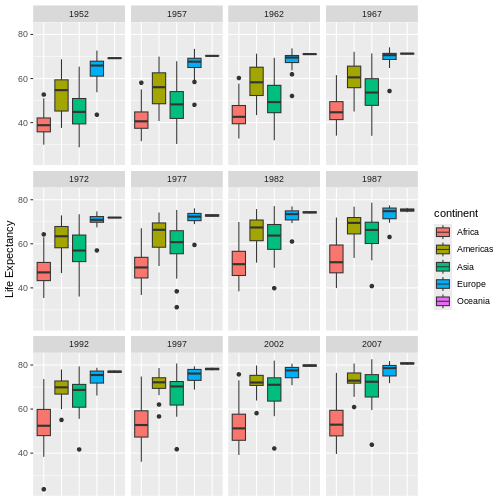

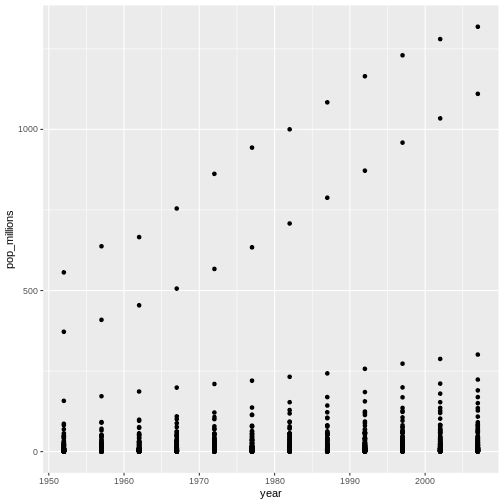

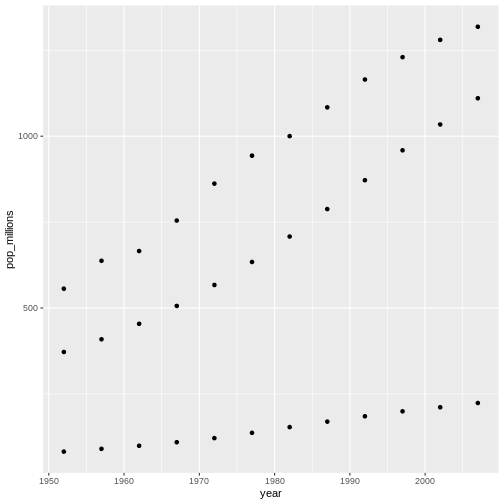

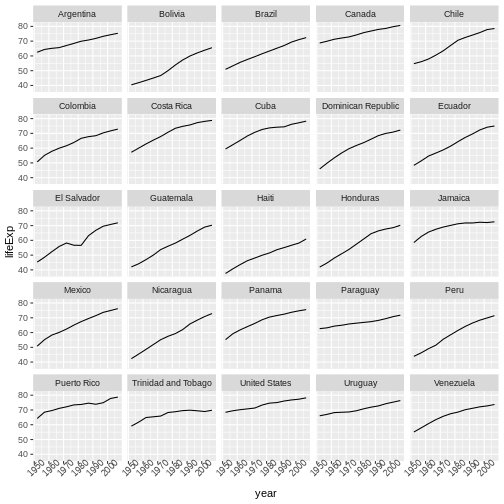

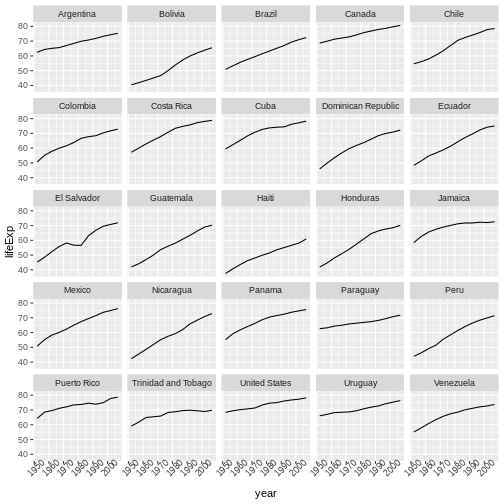

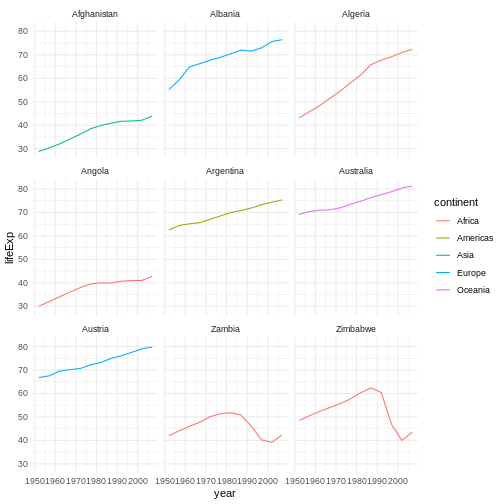

生データから始め、探索的な分析を行い、結果をグラフでプロットする方法を学びます。この例では、gapminder.orgのデータセットを使用し、時間を通じた各国の人口情報を扱います。データをRに読み込むことができますか?セネガルの人口をプロットできますか?アジア大陸の国々の平均所得を計算できますか?このレッスンの終わりまでに、これらの国々の人口を1分以内にプロットできるようになります!

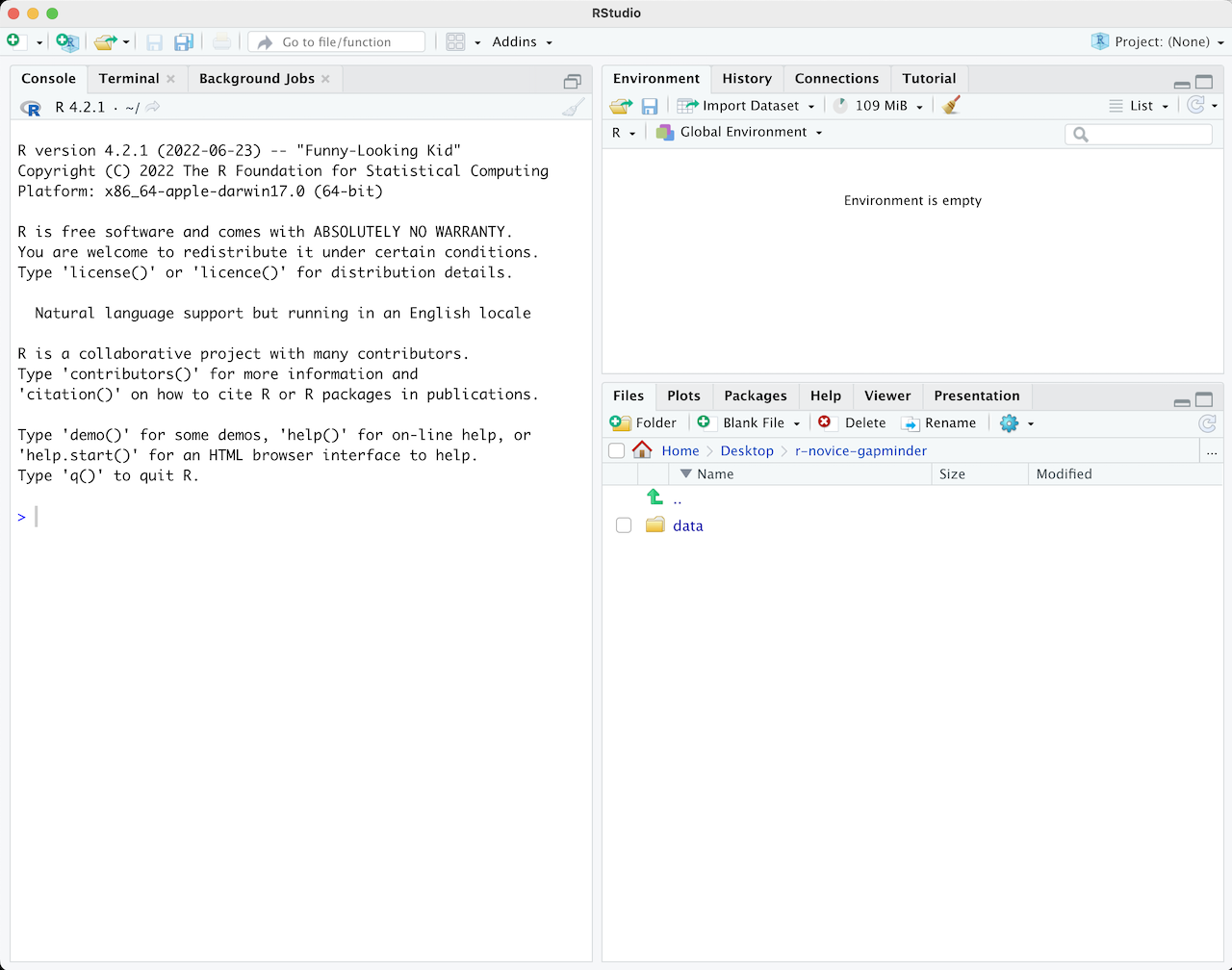

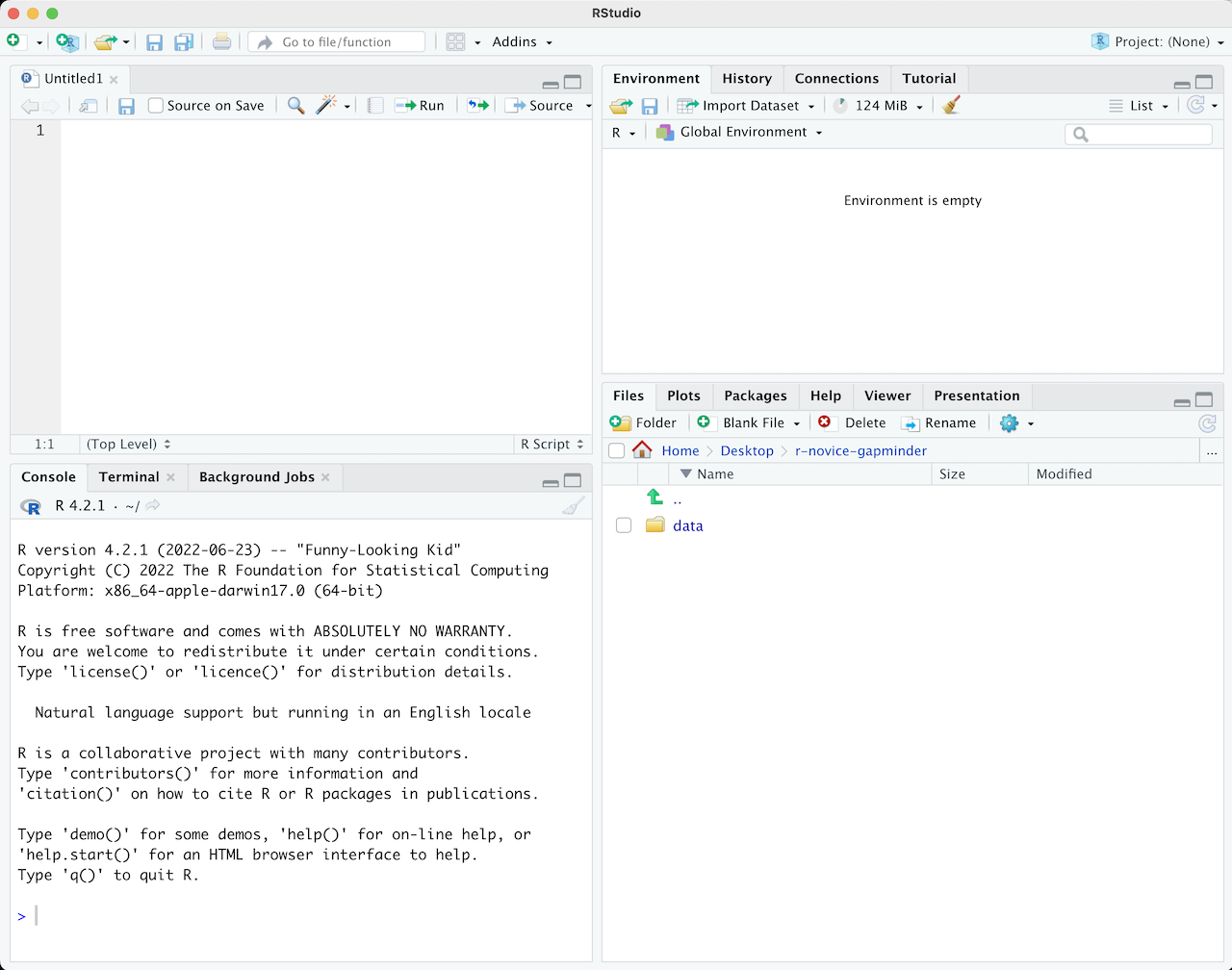

基本レイアウト

RStudioを初めて開くと、次の3つのパネルが表示されます:

- インタラクティブなRコンソール/ターミナル(左全体)

- 環境/履歴/接続(右上のタブ)

- ファイル/プロット/パッケージ/ヘルプ/ビューア(右下のタブ)

ファイル(例えばRスクリプト)を開くと、上部左にエディタパネルも表示されます。

Rスクリプト

Rコンソールに書いたコマンドはファイルに保存し、再実行することができます。このようなRコードを含むファイルをRスクリプトと呼びます。Rスクリプトは名前の末尾が.Rとなっており、それがRスクリプトであることを示します。

RStudio内でのワークフロー

RStudio内で作業する主な方法は2つあります:

- インタラクティブなRコンソール内でテストや試行を行い、そのコードをコピーして.Rファイルに貼り付け、後で実行する。

- 小規模なテストや初期の段階では効果的です。

- しかし、すぐに手間がかかるようになります。

- 最初から.Rファイルに記述し、RStudioのショートカットキーを使用して「Run」コマンドを実行し、現在の行、選択した行、または変更した行をインタラクティブなRコンソールに送る。

- これは作業を始める良い方法です。すべてのコードが後で使用するために保存されます。

- RStudio内またはRの

source()関数を使用して作成したファイルを実行できます。

ヒント:コードのセグメントを実行する

RStudioでは、エディタウィンドウからコードを実行する柔軟性があります。ボタン、メニューオプション、およびキーボードショートカットがあります。現在の行を実行するには、次の方法があります:

- エディタパネルの上部にある「Run」ボタンをクリックする

- 「Code」メニューから「Run Lines」を選択する

- WindowsまたはLinuxではCtrl+Return、OS Xでは⌘+Returnを押す (このショートカットはボタンの上にマウスをホバーさせると確認できます)。コードブロックを実行するには、選択して「Run」をクリックします。 最近実行したコードブロックを修正した場合、セクションを再選択して「Run」を押す必要はありません。次のボタン「Re-run the previous region」を使用すると、修正を含む前のコードブロックを実行できます。

R入門

Rでの作業の多くは、インタラクティブなRコンソール内で行います。ここでは、すべてのコードを実行し、Rスクリプトファイルに追加する前にアイデアを試すのに便利な環境です。RStudioのコンソールは、コマンドライン環境でRと入力した場合と同じです。

Rのインタラクティブセッションを開くと、最初に情報が表示され、その後に「>」と点滅するカーソルが現れます。これは、シェルレッスンで学んだシェル環境と多くの点で似ています。「Read, evaluate, print loop」(読み取り、評価、印刷ループ)の考え方に基づいて動作します:コマンドを入力すると、Rがそれを実行し、結果を返します。

Rを計算機として使う

Rで最も簡単なことは、算術を行うことです:

R

1 + 100

OUTPUT

[1] 101Rは答えを表示し、その前に”[1]“を付けます。[1]はコンソールに表示される行の最初の要素のインデックスを示します。ベクトルのインデックスについての詳細は、エピソード6:データのサブセット化を参照してください。

不完全なコマンドを入力すると、R

は完了を待機します。Unix Shellのbashに慣れている場合、この動作をbashで見たことがあるかもしれません。

OUTPUT

+「>」ではなく「+」が表示された場合、Rはコマンドの完了を待機しています。コマンドをキャンセルしたい場合はEscを押すと、RStudioは「>」プロンプトに戻ります。

ヒント:コマンドのキャンセル

コマンドラインからRを使用している場合は、RStudioの代わりにEscではなくCtrl+Cを使用してコマンドをキャンセルする必要があります。これはMacユーザーにも適用されます!

コマンドのキャンセルは、不完全なコマンドを終了させるだけでなく、予想以上に時間がかかる場合にコードの実行を停止したり、現在書いているコードを削除したりするためにも役立ちます。

Rを計算機として使用する場合、演算の順序は学校で学んだものと同じです。

優先順位が高いものから低いものへ:

- 括弧:

(,) - 累乗:

^または** - 乗算:

* - 除算:

/ - 加算:

+ - 減算:

-

R

3 + 5 * 2

OUTPUT

[1] 13評価の順序を変更したい場合や意図を明確にしたい場合は、括弧を使用してグループ化します。

R

(3 + 5) * 2

OUTPUT

[1] 16必要ない場合は煩雑になりますが、意図を明確にできます。他の人が後でコードを読むかもしれないことを忘れないでください。

R

(3 + (5 * (2 ^ 2))) # 読みにくい

3 + 5 * 2 ^ 2 # 規則を覚えていれば明快

3 + 5 * (2 ^ 2) # 規則を忘れた場合はこれが助けになる

各コード行の後にあるテキストは「コメント」と呼ばれます。ハッシュ記号#の後に続く内容は、コードを実行する際にRによって無視されます。

非常に小さいまたは大きい数値は、科学表記法で表示されます:

R

2/10000

OUTPUT

[1] 2e-04これは「10^XXで掛ける」という短縮形です。したがって、2e-4は2 * 10^(-4)の短縮形です。

科学表記法で数値を書くこともできます:

R

5e3 # マイナスがない点に注意

OUTPUT

[1] 5000数学関数

Rには多くの組み込み数学関数があります。関数を呼び出すには、関数名を入力し、その後に開き括弧と閉じ括弧を続けます。関数は引数を入力として受け取ります。関数の括弧内に入力したものはすべて引数と見なされます。関数によって引数の数は異なり、引数を必要としないものから複数の引数を必要とするものまであります。例:

R

getwd() # 絶対パスを返す

この例では引数は不要ですが、以下の数学関数では結果を計算するために値を渡す必要があります。

R

sin(1) # 三角関数

OUTPUT

[1] 0.841471R

log(1) # 自然対数

OUTPUT

[1] 0R

log10(10) # 常用対数(底10)

OUTPUT

[1] 1R

exp(0.5) # e^(1/2)

OUTPUT

[1] 1.648721Rのすべての関数を覚えようとする必要はありません。Googleで検索するか、関数名の最初の数文字を覚えていれば、RStudioのタブ補完機能を使うことができます。

RStudioの大きな利点の一つは、オートコンプリート機能があることです。これにより、関数、引数、および受け取る値を簡単に調べることができます。

コマンド名の前に?を付けると、そのコマンドのヘルプページが開きます。RStudioを使用している場合、’Help’ペインに表示されます。ターミナルでRを使用している場合は、ブラウザでヘルプページが開きます。ヘルプページにはコマンドの詳細な説明と動作の仕組みが含まれています。ページの下部までスクロールすると、通常、コマンドの使用例が掲載されています。後ほど例を見ていきます。

比較演算

Rでは比較を行うこともできます:

R

1 == 1 # 等しい(等号が2つ、"等しい"と読む)

OUTPUT

[1] TRUER

1 != 2 # 等しくない("等しくない"と読む)

OUTPUT

[1] TRUER

1 < 2 # より小さい

OUTPUT

[1] TRUER

1 <= 1 # 以下

OUTPUT

[1] TRUER

1 > 0 # より大きい

OUTPUT

[1] TRUER

1 >= -9 # 以上

OUTPUT

[1] TRUEヒント:数値の比較

数値を比較する際の注意点として、整数(小数を含まない数値型)以外を比較する場合は、==を使用しないでください。

コンピュータは小数を特定の精度でしか表現できないため、Rが表示する際に同じに見える2つの数値が、内部表現では異なる場合があります。このわずかな差異は「数値計算誤差(Machine numeric tolerance)」と呼ばれます。

代わりにall.equal関数を使用してください。

さらに詳しく知りたい方はこちら:http://floating-point-gui.de/

変数と代入

代入演算子<-を使用して、値を変数に格納できます:

R

x <- 1/40

代入は値を表示しません。代わりに、それを後で使用するために変数というものに格納します。この場合、xには値0.025が格納されています:

R

x

OUTPUT

[1] 0.025正確には、この格納された値は浮動小数点数と呼ばれる分数の10進数近似値です。

RStudioの右上ペインにあるEnvironmentタブを確認すると、xとその値が表示されていることがわかります。変数xは、数値を期待する計算の中で数値の代わりに使用できます:

R

log(x)

OUTPUT

[1] -3.688879また、変数には再代入も可能です:

R

x <- 100

以前はxに0.025が格納されていましたが、現在は100が格納されています。

代入値には、代入先の変数を含めることもできます:

R

x <- x + 1 # RStudioの右上タブでxの説明が更新されることに注目

y <- x * 2

代入の右辺には有効なR式を使用できます。右辺は代入が行われる前に完全に評価されます。

変数名には、文字、数字、アンダースコア、ピリオドを含めることができますが、スペースは含められません。また、変数名は文字またはピリオドで始める必要があります(数字やアンダースコアでは始めることはできません)。ピリオドで始まる変数は隠し変数と見なされます。

長い変数名については、異なる人が異なる規約を使用します。その例として:

- periods.between.words

- underscores_between_words

- camelCaseToSeparateWords

どれを使用するかは自由ですが、一貫性を保つことが重要です。

代入には=演算子を使用することも可能です:

R

x = 1/40

しかし、これはRユーザーの間ではあまり一般的ではありません。最も重要なのは、使用する演算子に一貫性を持つことです。<-を使用したほうが混乱が少ない場合もあり、コミュニティでは最も一般的に使われています。そのため、<-を使用することを推奨します。

ベクトル化

Rの特徴の1つに、Rがベクトル化されているという点があります。つまり、変数や関数にベクトルを値として持たせることができます。物理学や数学におけるベクトルとは異なり、Rにおけるベクトルは同じデータ型の値が順序付けられた集合を指します。例:

R

1:5

OUTPUT

[1] 1 2 3 4 5R

2^(1:5)

OUTPUT

[1] 2 4 8 16 32R

x <- 1:5

2^x

OUTPUT

[1] 2 4 8 16 32この機能は非常に強力で、今後のレッスンでさらに詳しく説明します。

環境の管理

Rセッションとやり取りするための便利なコマンドがいくつかあります。

lsを使用すると、グローバル環境(現在のRセッション)に保存されているすべての変数と関数を一覧表示できます:

R

ls()

OUTPUT

[1] "x" "y"ヒント:隠しオブジェクト

シェルと同様に、lsではデフォルトで”.”で始まる変数や関数は表示されません。すべてのオブジェクトを一覧表示するには、ls(all.names=TRUE)と入力してください。

ここでは、lsに引数を渡していませんが、関数を呼び出すために括弧は必要です。

lsだけを入力すると、オブジェクト一覧ではなくコードが表示されます:

R

ls

OUTPUT

function (name, pos = -1L, envir = as.environment(pos), all.names = FALSE,

pattern, sorted = TRUE)

{

if (!missing(name)) {

pos <- tryCatch(name, error = function(e) e)

if (inherits(pos, "error")) {

name <- substitute(name)

if (!is.character(name))

name <- deparse(name)

warning(gettextf("%s converted to character string",

sQuote(name)), domain = NA)

pos <- name

}

}

all.names <- .Internal(ls(envir, all.names, sorted))

if (!missing(pattern)) {

if ((ll <- length(grep("[", pattern, fixed = TRUE))) &&

ll != length(grep("]", pattern, fixed = TRUE))) {

if (pattern == "[") {

pattern <- "\\["

warning("replaced regular expression pattern '[' by '\\\\['")

}

else if (length(grep("[^\\\\]\\[<-", pattern))) {

pattern <- sub("\\[<-", "\\\\\\[<-", pattern)

warning("replaced '[<-' by '\\\\[<-' in regular expression pattern")

}

}

grep(pattern, all.names, value = TRUE)

}

else all.names

}

<bytecode: 0x559a24b4ffd0>

<environment: namespace:base>これはどういうことでしょうか?

Rではすべてがオブジェクトであり、オブジェクト名だけを入力すると、その内容が表示されます。先ほど作成したオブジェクトxには1,

2, 3, 4, 5が格納されています:

R

x

OUTPUT

[1] 1 2 3 4 5オブジェクトlsには、ls関数を動作させるRコードが格納されています!関数の仕組みや作成方法については後のレッスンで説明します。

不要になったオブジェクトを削除するには、rmを使用します:

R

rm(x)

多くのオブジェクトが環境にあり、それらをすべて削除したい場合は、lsの結果をrm関数に渡します:

R

rm(list = ls())

この場合、2つの関数を組み合わせています。演算の順序と同様に、最も内側の括弧内の内容が最初に評価されます。

この場合、lsの結果がrmのlist引数として使用されるよう指定しています。引数に値を名前で割り当てる場合、必ず=演算子を使用する必要があります!

代わりに<-を使用すると、予期しない副作用が発生するか、エラーメッセージが表示される可能性があります:

R

rm(list <- ls())

ERROR

Error in rm(list <- ls()): ... must contain names or character stringsヒント:警告とエラー

Rが予期しない動作をした場合は注意してください!エラーはRが計算を続行できない場合に発生します。一方、警告は通常、関数が実行されたものの、期待通りに動作しなかったことを意味します。

どちらの場合も、Rが表示するメッセージには問題を解決するための手がかりが含まれていることが多いです。

Rパッケージ

Rにはパッケージを作成することで関数を追加することができます。また、他の人が作成したパッケージを利用することも可能です。この執筆時点で、CRAN(Comprehensive R Archive Network)には10,000を超えるパッケージが利用可能です。RとRStudioにはパッケージを管理するための機能があります:

- インストールされているパッケージを確認するには、

installed.packages()を入力します。 - パッケージをインストールするには、

install.packages("packagename")と入力します。ここでpackagenameはパッケージ名で、引用符で囲みます。 - インストール済みのパッケージを更新するには、

update.packages()を入力します。 - パッケージを削除するには、

remove.packages("packagename")を使用します。 - パッケージを利用可能にするには、

library(packagename)を入力します。

RStudioの右下ペインの「Packages」タブからもパッケージを表示、ロード、デタッチすることができます。このタブをクリックすると、インストール済みのパッケージがチェックボックス付きで表示されます。パッケージ名の横にあるチェックボックスがオンの場合、そのパッケージはロードされており、オフの場合はロードされていません。空のボックスをクリックするとそのパッケージがロードされ、チェックボックスをクリックするとパッケージがデタッチされます。

また、「Packages」タブの上部にある「Install」ボタンと「Update」ボタンを使用して、パッケージをインストールおよび更新できます。

チャレンジ 2

次のプログラムの各文の後で、各変数の値はどうなるでしょうか?

R

mass <- 47.5

age <- 122

mass <- mass * 2.3

age <- age - 20

R

mass <- 47.5

この時点で変数massの値は47.5になります。

R

age <- 122

この時点で変数ageの値は122になります。

R

mass <- mass * 2.3

既存の値47.5に2.3を掛け、新しい値109.25をmassに格納します。

R

age <- age - 20

既存の値122から20を引き、新しい値102をageに格納します。

チャレンジ 3

前のチャレンジのコードを実行し、massとageを比較するコマンドを書きなさい。massはageより大きいですか?

この質問に答える方法の1つとして、次のように>を使用できます:

R

mass > age

OUTPUT

[1] TRUEこのコードは、109.25が102より大きいため、論理値TRUEを返すはずです。

チャレンジ 4

作業環境を整理し、massとageの変数を削除しなさい。

このタスクを達成するには、rmコマンドを使用します:

R

rm(age, mass)

チャレンジ 5

以下のパッケージをインストールしなさい:ggplot2,

plyr, gapminder

必要なパッケージをインストールするには、install.packages()コマンドを使用します。

R

install.packages("ggplot2")

install.packages("plyr")

install.packages("gapminder")

1つのinstall.packages()コマンドで複数のパッケージ

をインストールする別の方法は次のとおりです:

R

install.packages(c("ggplot2", "plyr", "gapminder"))

- RStudioを使用してRプログラムを作成および実行します。

- Rには通常の算術演算子と数学関数があります。

-

<-を使用して変数に値を代入します。 -

ls()を使用してプログラム内の変数を一覧表示します。 -

rm()を使用してプログラム内のオブジェクトを削除します。 -

install.packages()を使用してパッケージ(ライブラリ)をインストールします。

Content from RStudio を使ったプロジェクト管理

Last updated on 2025-11-11 | Edit this page

Overview

Questions

- R でプロジェクトをどのように管理できますか?

Objectives

- RStudio で自己完結型のプロジェクトを作成する

はじめに

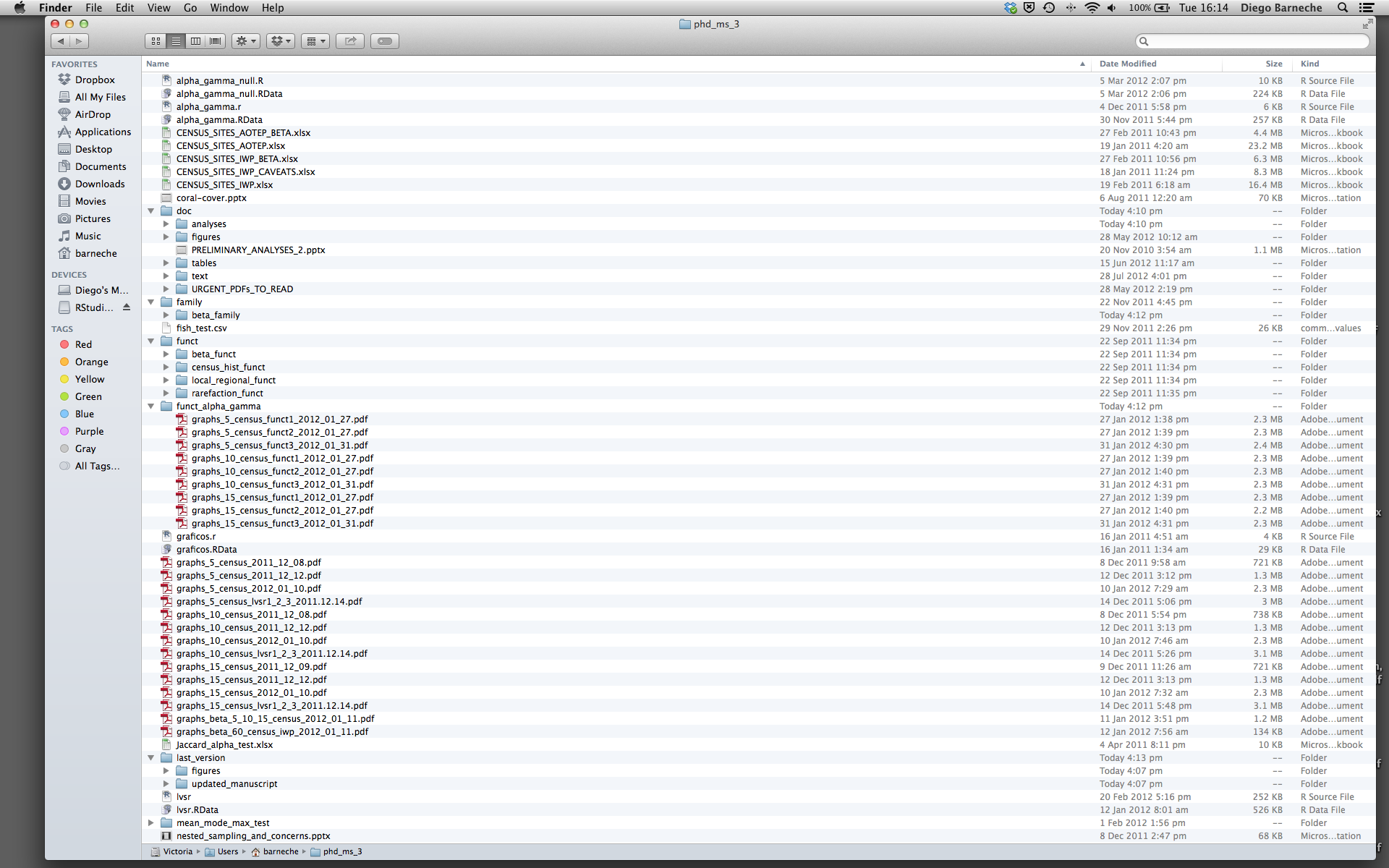

科学的なプロセスは本質的に段階的なものであり、多くのプロジェクトはランダムなメモ、一部のコード、次に原稿と進行し、最終的にはすべてが混ざり合ってしまうことがよくあります。

プロジェクトを再現可能な方法で管理することは、科学を再現可能にするだけでなく、生活をより簡単にします。

— Vince Buffalo (@vsbuffalo) 2013年4月15日

ほとんどの人はプロジェクトを次のように整理しがちです:

このような方法を絶対に避けるべき理由は数多くあります:

- データのどのバージョンがオリジナルで、どれが修正済みなのかを区別するのが非常に難しい。

- 様々な拡張子のファイルが混在して、非常に散らかる。

- 必要なものを見つけたり、正確なコードで生成した正しい図表を関連付けたりするのに非常に時間がかかる。

良いプロジェクト構成は、最終的に生活をより簡単にします:

- データの整合性を確保しやすくなる。

- 他の人(研究室の同僚、共同研究者、指導教員)とコードを共有するのが簡単になる。

- 原稿の投稿時にコードを簡単にアップロードできる。

- しばらく休んだ後にプロジェクトを再開しやすくなる。

考えられる解決策

幸いなことに、作業を効果的に管理するためのツールやパッケージが存在します。

RStudio の最も強力で便利な機能の一つがプロジェクト管理機能です。本日はこれを使って自己完結型の再現可能なプロジェクトを作成します。

チャレンジ 1: 自己完結型プロジェクトの作成

RStudio で新しいプロジェクトを作成します:

- 「File」メニューをクリックし、「New Project」を選択します。

- 「New Directory」をクリックします。

- 「New Project」をクリックします。

- プロジェクトを保存するディレクトリの名前(例:

my_project)を入力します。 - 「Create a git repository」のチェックボックスが表示される場合は選択します。

- 「Create Project」ボタンをクリックします。

作成した RStudio

プロジェクトを開く最も簡単な方法は、ファイルシステムをたどって保存したディレクトリに移動し、.Rproj

ファイルをダブルクリックすることです。これにより RStudio が開き、R

セッションが .Rproj

ファイルと同じディレクトリで開始します。データ、プロット、スクリプトはすべてプロジェクトディレクトリに関連付けられます。さらに、RStudio

プロジェクトは複数のプロジェクトを同時に開くことが可能で、それぞれのプロジェクトディレクトリに分離されます。これにより、複数のプロジェクトを開いても相互に干渉しません。

チャレンジ 2: ファイルシステムを使った RStudio プロジェクトの開き方

- RStudio を終了します。

- チャレンジ 1 で作成したプロジェクトのディレクトリに移動します。

- そのディレクトリ内の

.Rprojファイルをダブルクリックします。

プロジェクト管理のベストプラクティス

プロジェクトを整理するための「ベスト」な方法はありませんが、管理を容易にするために従うべきいくつかの一般原則があります:

データを読み取り専用として扱う

プロジェクトを設定する際の最も重要な目標はこれです。データの収集は通常、時間と費用がかかります。データをインタラクティブに操作する(例:Excel で)と、データの出所や収集後にどのように変更されたかを把握できなくなります。そのため、データを「読み取り専用」として扱うのが良い考えです。

データのクリーニング

多くの場合、データは「汚れて」おり、R(または他のプログラミング言語)で有用な形式にするために大幅な前処理が必要です。このタスクは「データマンジング」と呼ばれることもあります。これらのスクリプトを別のフォルダに保存し、クリーンなデータセットを保持する「読み取り専用」データフォルダを作成することで、両者の混同を防ぐことができます。

生成された出力を使い捨てとみなす

スクリプトによって生成されたものはすべて使い捨てとみなすべきです:スクリプトからすべてを再生成できる必要があります。

出力を管理する方法はたくさんあります。各分析ごとに異なるサブディレクトリを持つ出力フォルダを用意すると、後で便利です。多くの分析は探索的で最終プロジェクトに使用されないことが多く、一部の分析はプロジェクト間で共有されることもあります。

ヒント: 科学的コンピューティングのための「十分に良い」実践

科学的コンピューティングのための「十分に良い」実践 では、プロジェクトの構成について以下の推奨事項を挙げています:

- 各プロジェクトを専用のディレクトリに配置し、そのディレクトリにプロジェクト名を付ける。

- プロジェクトに関連するテキスト文書を

docディレクトリに配置する。 - 生データとメタデータを

dataディレクトリに、クリーンアップや分析中に生成されたファイルをresultsディレクトリに配置する。 - プロジェクトのスクリプトやプログラムのソースを

srcディレクトリに配置し、他から持ち込んだプログラムやローカルでコンパイルしたプログラムをbinディレクトリに配置する。 - すべてのファイルに内容や機能を反映した名前を付ける。

関数の定義と適用を分離する

R を効率的に使用する最も効果的な方法の一つは、最初に .R スクリプトに実行したいコードを書き、RStudio のキーボードショートカットを使用するか「Run」ボタンをクリックして、選択した行をインタラクティブな R コンソールで実行することです。

プロジェクトの初期段階では、最初の .R スクリプトファイルに多くの直接実行されるコード行が含まれることがよくあります。プロジェクトが進むにつれて、再利用可能なコードチャンクが独自の関数に分離されます。これらの関数を保存するためのフォルダと分析スクリプトを保存するためのフォルダを分けるのが良いアイデアです。

データを data ディレクトリに保存する

良好なディレクト

リ構造ができたら、データファイルを data/

ディレクトリに保存します。

チャレンジ 3

このリンクから CSV ファイルをダウンロードしてください。

- ファイルをダウンロードします(上記リンクを右クリック -> 「リンク先を名前を付けて保存」/「名前を付けて保存」、またはリンクをクリックしページが読み込まれた後に Ctrl+S を押すか、メニューの「ファイル」 -> 「ページを名前を付けて保存」を選択)。

-

gapminder_data.csvという名前で保存されていることを確認します。 - ファイルをプロジェクト内の

data/フォルダに保存します。

後ほどこのデータを読み込み、確認します。

チャレンジ 4

R に読み込む前に、コマンドラインからデータセットについての一般的な情報を得ることは有益です。これにより、R に読み込む際の判断に役立ちます。コマンドラインシェルを使用して以下の質問に答えてください:

- ファイルのサイズはどれくらいですか?

- このファイルには何行のデータがありますか?

- このファイルにはどのような値が含まれていますか?

次のコマンドをシェルで実行します:

OUTPUT

-rw-r--r-- 1 runner runner 80K Nov 11 00:28 data/gapminder_data.csvファイルサイズは 80K です。

OUTPUT

1705 data/gapminder_data.csv行数は 1705 行です。データの内容は次のようになります:

OUTPUT

country,year,pop,continent,lifeExp,gdpPercap

Afghanistan,1952,8425333,Asia,28.801,779.4453145

Afghanistan,1957,9240934,Asia,30.332,820.8530296

Afghanistan,1962,10267083,Asia,31.997,853.10071

Afghanistan,1967,11537966,Asia,34.02,836.1971382

Afghanistan,1972,13079460,Asia,36.088,739.9811058

Afghanistan,1977,14880372,Asia,38.438,786.11336

Afghanistan,1982,12881816,Asia,39.854,978.0114388

Afghanistan,1987,13867957,Asia,40.822,852.3959448

Afghanistan,1992,16317921,Asia,41.674,649.3413952ヒント: RStudio のコマンドライン

RStudio のコンソールペインにある「Terminal」タブを使用すると、RStudio 内で直接コマンドラインを操作できます。

作業ディレクトリ

R の現在の作業ディレクトリを知ることは重要です。なぜなら、他のファイルにアクセスする必要があるとき(例:データファイルをインポートする場合)、R は現在の作業ディレクトリを基準にそれらのファイルを探すからです。

新しい RStudio

プロジェクトを作成するたびに、そのプロジェクトの新しいディレクトリが作成されます。既存の

.Rproj ファイルを開くと、そのプロジェクトが開き、R

の作業ディレクトリがそのファイルがあるフォルダに設定されます。

チャレンジ 5

getwd() コマンドを使用するか、RStudio

のメニューを使って現在の作業ディレクトリを確認します。

- コンソールで

getwd()(“wd” は “working directory” の略)と入力し、Enter を押します。 - ファイルペインで、

dataフォルダをダブルクリックして開く(または他の任意のフォルダに移動)。作業ディレクトリに戻るには、ファイルペインの「More」をクリックし、「Go To Working Directory」を選択します。

setwd() コマンドを使用するか、RStudio

のメニューを使って作業ディレクトリを変更します。

- コンソールで

setwd("data")と入力し、Enter を押します。その後、getwd()と入力して Enter を押し、新しい作業ディレクトリを確認します。 - RStudio ウィンドウ上部のメニューで「Session」をクリックし、「Set

Working Directory」を選択して「Choose

Directory」をクリックします。その後、開いたウィンドウでプロジェクトディレクトリに戻り、「Open」をクリックします。コンソールに

setwdコマンドが自動的に表示されます。

ヒント: ファイルが存在しないエラー

R コードでファイルを参照しようとして「ファイルが存在しない」というエラーが出た場合は、作業ディレクトリを確認するのが良いです。 ファイルへの絶対パスを指定するか、作業ディレクトリ内(またはそのサブフォルダ)にファイルを保存し、相対パスを指定する必要があります。

バージョン管理

プロジェクトではバージョン管理を使用することが重要です。RStudio で Git を使用する方法についての良いレッスンはこちらを参照してください。

- RStudio を使用して一貫したレイアウトでプロジェクトを作成および管理する。

- 生データを読み取り専用として扱う。

- 生成された出力を使い捨てとみなす。

- 関数の定義と適用を分離する。

Content from ヘルプの利用

Last updated on 2025-11-11 | Edit this page

Overview

Questions

- R でどのようにしてヘルプを得ることができますか?

Objectives

- 関数や特殊な演算子に関する R のヘルプファイルを読むことができる。

- 問題を解決するためのパッケージを特定するために CRAN タスクビューを利用できる。

- 仲間に助けを求める方法を理解する。

ヘルプファイルを読む

R および各パッケージには関数用のヘルプファイルが用意されています。特定のパッケージに含まれる関数についてヘルプを検索する際の一般的な構文は次の通りです:

R

?function_name

help(function_name)

たとえば、write.table()

のヘルプファイルを見てみましょう。この関数に似た機能を持つ関数を今後のエピソードで使用します。

R

?write.table()

これにより、RStudio ではヘルプページが表示され、R 本体ではプレーンテキストとして表示されます。

各ヘルプページは次のようなセクションに分かれています:

- Description(説明): 関数が何をするかの詳細な説明。

- Usage(使用法): 関数の引数とそのデフォルト値(変更可能)。

- Arguments(引数): 各引数が期待するデータの説明。

- Details(詳細): 注意すべき重要な点。

- Value(戻り値): 関数が返すデータ。

- See Also(関連項目): 有用な関連関数。

- Examples(例): 関数の使用例。

関数によってはセクションが異なる場合がありますが、これらが主なポイントです。

関連する関数が同じヘルプファイルを参照する場合があることに注意してください:

R

?write.table()

?write.csv()

これらの関数は非常に似た用途を持ち、引数も共通しているため、パッケージ作者が同じヘルプファイルで文書化していることがよくあります。

ヒント: 実例を実行する

ヘルプページ内の Examples セクションからコードをハイライトして Ctrl+Return を押すと、RStudio コンソールで実行されます。 関数の動作を素早く理解する方法です。

ヒント: ヘルプファイルを読む

R の大きな課題の一つは、利用可能な関数の数が膨大であることです。 すべての関数の正しい使用法を記憶するのは現実的ではありません。 しかし、ヘルプファイルを利用すれば、記憶する必要はありません!

特殊な演算子

特殊な演算子に関するヘルプを検索するには、引用符またはバッククォートを使用します:

R

?"<-"

?`<-`

パッケージに関するヘルプ

多くのパッケージには「ビネット」と呼ばれるチュートリアルや拡張的な例のドキュメントが含まれています。

引数なしで vignette()

を実行すると、インストール済みのすべてのパッケージのビネットが表示されます。

特定のパッケージについては vignette(package="パッケージ名")

を使用します。 特定のビネットを開くには

vignette("ビネット名") を実行します。

パッケージにビネットがない場合は、通常、次のコマンドでヘルプを探せます:

R

help("パッケージ名")

また、RStudio には多くのパッケージ向けに優れた チートシート があります。

関数名の一部を覚えている場合

関数がどのパッケージに属しているか、または正確なスペルがわからない場合、ファジー検索が可能です:

R

??function_name

ファジー検索では文字列の近似一致を検索します。たとえば、作業ディレクトリを設定する関数に「set」が含まれていることを覚えている場合、次のように検索できます:

R

??set

どこから始めるべきかわからない場合

どの関数やパッケージを使用すべきかわからない場合、 CRAN Task Views を利用するとよいでしょう。 これは、パッケージを分野別にグループ化した特別なリストで、出発点として適しています。

コードが動作しない場合: 仲間に助けを求める

関数の使用に問題がある場合、その答えのほとんどはすでに Stack Overflow

で回答されています。 [r]

タグを使って検索してください。質問の仕方については、Stack Overflow の 良い質問の仕方のページを参照してください。

答えが見つからない場合、以下の便利な関数を使って仲間に助けを求めるとよいでしょう:

R

?dput

この関数は、使用しているデータを他の人が自分の R セッションでコピー&ペーストできる形式に出力します。

R

sessionInfo()

OUTPUT

R version 4.5.2 (2025-10-31)

Platform: x86_64-pc-linux-gnu

Running under: Ubuntu 22.04.5 LTS

Matrix products: default

BLAS: /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/blas/libblas.so.3.10.0

LAPACK: /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/lapack/liblapack.so.3.10.0 LAPACK version 3.10.0

locale:

[1] LC_CTYPE=C.UTF-8 LC_NUMERIC=C LC_TIME=C.UTF-8

[4] LC_COLLATE=C.UTF-8 LC_MONETARY=C.UTF-8 LC_MESSAGES=C.UTF-8

[7] LC_PAPER=C.UTF-8 LC_NAME=C LC_ADDRESS=C

[10] LC_TELEPHONE=C LC_MEASUREMENT=C.UTF-8 LC_IDENTIFICATION=C

time zone: UTC

tzcode source: system (glibc)

attached base packages:

[1] stats graphics grDevices utils datasets methods base

loaded via a namespace (and not attached):

[1] compiler_4.5.2 tools_4.5.2 yaml_2.3.10 knitr_1.48 xfun_0.49

[6] renv_1.1.5 evaluate_1.0.1この関数は、R の現在のバージョンやロードしているパッケージを表示します。 これは他の人が問題を再現し、デバッグするのに役立ちます。

チャレンジ 1

c

関数のヘルプページを見てください。次のコードを評価した場合、どのようなベクトルが作成されると思いますか?

R

c(1, 2, 3)

c('d', 'e', 'f')

c(1, 2, 'f')

c()

関数はすべての要素が同じ型のベクトルを作成します。最初の場合、要素は数値型、

2 番目の場合は文字型、そして 3

番目の場合も文字型です。数値型の値は文字型に「強制変換」されます。

チャレンジ 2

paste

関数のヘルプを見てください。この関数を後ほど使用します。

sep 引数と collapse 引数の違いは何ですか?

paste() 関数のヘルプを見るには以下を実行します:

R

help("paste")

?paste

sep と collapse

の違いは少し複雑です。paste

関数は任意の数の引数を受け取り、それぞれが任意の長さのベクトルであることができます。

sep

引数は連結される各項目の間に使用される文字列を指定します(デフォルトはスペース)。

結果は、paste

に渡された最も長い引数と同じ長さのベクトルです。

一方、collapse

引数は、連結後の要素を指定された区切り文字を使用して「まとめて結合」することを示します。

その結果、単一の文字列になります。

引数を明示的に指定することが重要です。たとえば sep = ","

と入力すると、関数は区切り文字として “,”

を使用し、結合する項目としてではないと認識します。

例:

R

paste(c("a","b"), "c")

OUTPUT

[1] "a c" "b c"R

paste(c("a","b"), "c", ",")

OUTPUT

[1] "a c ," "b c ,"R

paste(c("a","b"), "c", sep = ",")

OUTPUT

[1] "a,c" "b,c"R

paste(c("a","b"), "c", collapse = "|")

OUTPUT

[1] "a c|b c"R

paste(c("a","b"), "c", sep = ",", collapse = "|")

OUTPUT

[1] "a,c|b,c"(詳細については、?paste

ヘルプページの末尾の例を参照するか、example('paste')

を試してください。)

チャレンジ 3

ヘルプを使用して、タブ区切り(\t)の列と小数点が

“.”(ピリオド)で表される表形式のファイルを読み込むために使用できる関数(および関連するパラメータ)を見つけてください。

特に国際的な同僚と協力している場合、小数点の表記(例:コンマ対ピリオド)は異なる場合があるため、この確認が重要です。

ヒント:??"read table"

を使用して表形式データの読み込みに関連する関数を調べてください。

タブ区切りファイルを小数点がピリオドで表される形式で読み込む標準的な

R 関数は read.delim() です。

また、read.table(file, sep="\t")

を使用することもできます(read.table()

のデフォルトの小数点はピリオドです)。

ただし、データファイルにハッシュ(#)文字が含まれている場合は、comment.char

引数を変更する必要があるかもしれません。

その他のリソース

- R のオンラインヘルプを取得するには

help()を使用します。

Content from データ構造

Last updated on 2025-11-11 | Edit this page

Overview

Questions

- R でデータをどのように読み取ることができますか?

- R の基本的なデータ型は何ですか?

- R でカテゴリ情報をどのように表現しますか?

Objectives

- 5 つの主なデータ型を特定できるようになる。

- データフレームを探索し始め、ベクトルやリストとの関連を理解する。

- R からオブジェクトの型、クラス、構造に関する質問ができるようになる。

- “names”、“class”、“dim” 属性の情報を理解する。

R の最も強力な機能の 1 つは、スプレッドシートや CSV

ファイルにすでに保存されているような表形式データを処理する能力です。まずは、data/

ディレクトリに feline-data.csv

という名前の小さなデータセットを作成しましょう:

R

cats <- data.frame(coat = c("calico", "black", "tabby"),

weight = c(2.1, 5.0, 3.2),

likes_catnip = c(1, 0, 1))

次に、cats を CSV

ファイルとして保存します。引数名を明示的に指定することは良い習慣であり、関数が変更されたデフォルト値を認識できます。この場合は

row.names = FALSE

を設定しています。引数名やそのデフォルト値を確認するには、?write.csv

を使用してヘルプファイルを表示してください。

R

write.csv(x = cats, file = "data/feline-data.csv", row.names = FALSE)

新しいファイル feline-data.csv

の内容は次の通りです:

ヒント: R でテキストファイルを編集する

または、テキストエディタ(Nano)や RStudio の File -> New

File -> Text File メニュー項目を使用して

data/feline-data.csv を作成することもできます。

このデータを R に読み込むには、以下のコマンドを使用します:

R

cats <- read.csv(file = "data/feline-data.csv")

cats

OUTPUT

coat weight likes_catnip

1 calico 2.1 1

2 black 5.0 0

3 tabby 3.2 1read.table 関数は、CSV ファイル(csv = comma-separated

values)などのテキストファイルに保存された表形式データを読み取るために使用されます。タブやカンマは、CSV

ファイルでデータポイントを区切るために最も一般的に使用される記号です。R

では read.table の便利なバージョンとして

read.csv(データがカンマで区切られている場合)と

read.delim(データがタブで区切られている場合)が用意されています。この

3 つの中で、read.csv

が最も一般的に使用されます。必要に応じて、デフォルトの区切り記号を変更することもできます。

データが因子かどうかを確認する

最近、R がテキストデータを処理する方法が変更されました。以前は、R はテキストデータを自動的に “因子” という形式に変換していましたが、現在は “文字列” という形式で処理されるようになりました。因子の使用用途については後ほど学びますが、ほとんどの場合は必要なく、使用することで複雑になるだけです。そのため、新しい R バージョンではテキストデータが “文字列” として読み取られます。因子が自動的に作成されているかを確認し、必要に応じて文字列形式に変換してください:

- 入力データの型を確認するには、

str(cats)を入力します。 - 出力で、コロンの後にある 3

文字のコードを確認します:

numとchrのみが表示される場合は、レッスンを続けることができます。このボックスはスキップしてください。fctが見つかった場合は、次の手順に進んでください。 - R

が因子データを自動的に作成しないようにするには、以下のコードを実行します:

options(stringsAsFactors = FALSE)。その後、catsテーブルを再読み込みして変更を反映させます。 - R を再起動するたびに、このオプションを設定する必要があります。忘れないように、データを読み込む前にスクリプトの最初の行のいずれかに含めてください。

- R バージョン 4.0.0 以降では、テキストデータは因子に変換されなくなりました。問題を回避するためにこのバージョン以降をインストールすることを検討してください。研究所や会社のコンピュータを使用している場合は、管理者に依頼してください。

データセットをすぐに探索し始めることができます。たとえば、$

演算子を使用して列を指定します:

R

cats$weight

OUTPUT

[1] 2.1 5.0 3.2R

cats$coat

OUTPUT

[1] "calico" "black" "tabby" 列に対して操作を実行することもできます:

R

## たとえば、スケールが 2kg 軽いことが判明した場合:

cats$weight + 2

OUTPUT

[1] 4.1 7.0 5.2R

paste("My cat is", cats$coat)

OUTPUT

[1] "My cat is calico" "My cat is black" "My cat is tabby" しかし、次のコードではどうでしょうか?

R

cats$weight + cats$coat

ERROR

Error in cats$weight + cats$coat: non-numeric argument to binary operatorここで何が起こったのかを理解することが、R でデータを成功裏に分析する鍵です。

データ型

最後のコマンドがエラーを返す理由が 2.1 と

"black"

を加算するのは無意味だからだと推測したなら、あなたは正しいです!これはプログラミングにおける重要な概念である

データ型

に関する直感をすでに持っているということです。データの型を調べるには、次のように入力します:

R

typeof(cats$weight)

OUTPUT

[1] "double"主なデータ型は次の 5

種類です:double、integer、complex、logical、character。

歴史的な理由で、double は numeric

とも呼ばれます。

R

typeof(3.14)

OUTPUT

[1] "double"R

typeof(1L) # L サフィックスを付けると数値を整数に強制します(R はデフォルトで浮動小数点数を使用)

OUTPUT

[1] "integer"R

typeof(1+1i)

OUTPUT

[1] "complex"R

typeof(TRUE)

OUTPUT

[1] "logical"R

typeof('banana')

OUTPUT

[1] "character"分析がどれだけ複雑であっても、R ではすべてのデータがこれらの基本的なデータ型のいずれかとして解釈されます。この厳格さには非常に重要な意味があります。

別の猫の詳細を追加した情報が、ファイル

data/feline-data_v2.csv に保存されています。

R

file.show("data/feline-data_v2.csv")

この新しい猫データを以前と同じ方法で読み込み、weight

列にどのようなデータ型が含まれているか確認します:

R

cats <- read.csv(file="data/feline-data_v2.csv")

typeof(cats

$weight)

OUTPUT

[1] "character"あらら、weight 列の型が double

ではなくなっています!以前と同じ計算を試みると、問題が発生します:

R

cats$weight + 2

ERROR

Error in cats$weight + 2: non-numeric argument to binary operator何が起こったのでしょうか? 私たちが扱っている cats

データは データフレーム と呼ばれるものです。データフレームは、R

で最も一般的で多用途な データ構造 の 1 つです。

データフレームの特定の列には異なるデータ型を混在させることはできません。

この場合、R はデータフレーム列 weight のすべてを

double

として読み取らなかったため、列全体のデータ型がその列内のすべてに適した型に変わります。

R が CSV ファイルを読み取ると、それは データフレーム

として読み込まれます。そのため、cats CSV

ファイルを読み込むと、データフレームとして保存されます。データフレームは

str() 関数によって表示される最初の行で認識できます:

R

str(cats)

OUTPUT

'data.frame': 4 obs. of 3 variables:

$ coat : chr "calico" "black" "tabby" "tabby"

$ weight : chr "2.1" "5" "3.2" "2.3 or 2.4"

$ likes_string: int 1 0 1 1データフレーム は行と列で構成され、各列は同じ数の行を持ちます。データフレームの異なる列は異なるデータ型で構成できます(これがデータフレームを非常に柔軟にする理由です)が、特定の列内ではすべてが同じ型である必要があります(例:ベクトル、因子、リストなど)。

この振る舞いをさらに調査する間、猫のデータから余分な行を削除し、それを再読み込みしましょう:

feline-data.csv:

coat,weight,likes_catnip

calico,2.1,1

black,5.0,0

tabby,3.2,1そして RStudio 内で:

R

cats <- read.csv(file="data/feline-data.csv")

ベクトルと型の強制変換

この挙動をよりよく理解するために、別のデータ構造である ベクトル を紹介します。

R

my_vector <- vector(length = 3)

my_vector

OUTPUT

[1] FALSE FALSE FALSER

におけるベクトルは、基本的に順序付けられた要素のリストです。ただし、特別な条件として、ベクトル内のすべての要素は同じ基本データ型である必要があります。データ型を指定しない場合、デフォルトで

logical

型になります。また、任意の型の空のベクトルを宣言することも可能です。

R

another_vector <- vector(mode='character', length=3)

another_vector

OUTPUT

[1] "" "" ""あるオブジェクトがベクトルかどうかを確認することもできます:

R

str(another_vector)

OUTPUT

chr [1:3] "" "" ""このコマンドのやや難解な出力は、このベクトルに含まれる基本データ型(この場合は

chr、文字型)を示し、ベクトル内の要素数(この場合は

[1:3])、および実際に含まれる要素(この場合は空の文字列)を示します。同様に次のコマンドを実行すると、

R

str(cats$weight)

OUTPUT

num [1:3] 2.1 5 3.2cats$weight もベクトルであることがわかります。R

のデータフレームに読み込まれる列はすべてベクトルです。これが、R

が列内のすべての要素を同じ基本データ型に強制する理由の根本です。

討論 1

なぜ R は列に含まれるデータに対してこれほど厳格なのでしょうか? この厳格さは私たちにどのように役立つのでしょうか?

列内のすべてのデータが同じであることで、データに対して単純な仮定を行うことができます。たとえば、列の 1 つの要素を数値として解釈できるなら、列内のすべての要素を数値として解釈できます。そのため、毎回確認する必要がなくなります。この一貫性こそが、人々が「クリーンデータ」と呼ぶものです。長い目で見ると、この厳格な一貫性は R におけるデータ操作を非常に簡単にしてくれます。

ベクトルを結合する際の型の強制変換

明示的な内容を持つベクトルを c()

関数で作成できます:

R

combine_vector <- c(2,6,3)

combine_vector

OUTPUT

[1] 2 6 3これまで学んだ内容を考えると、次のコードは何を生成すると思いますか?

R

quiz_vector <- c(2,6,'3')

これは 型の強制変換

と呼ばれるもので、予想外の結果をもたらすことがあり、基本データ型と R

がそれをどのように解釈するかを理解する必要があります。R

は、異なる型(ここでは double と

character)が単一のベクトルに結合される場合、それらをすべて同じ型に強制します。例を見てみましょう:

R

coercion_vector <- c('a', TRUE)

coercion_vector

OUTPUT

[1] "a" "TRUE"R

another_coercion_vector <- c(0, TRUE)

another_coercion_vector

OUTPUT

[1] 0 1型の階層

型の強制変換ルールは次の通りです:logical -> integer ->

double (“numeric”) -> complex

-> character

この矢印は「変換される」と読めます。たとえば、logical

と character を結合すると、結果は character

に変換されます:

R

c('a', TRUE)

OUTPUT

[1] "a" "TRUE"character

ベクトルは、印刷時にクォートで囲まれていることで簡単に認識できます。

逆方向の強制変換を試みる場合は、as.

関数を使用します:

R

character_vector_example <- c('0','2','4')

character_vector_example

OUTPUT

[1] "0" "2" "4"R

character_coerced_to_double <- as.double(character_vector_example)

character_coerced_to_double

OUTPUT

[1] 0 2 4R

double_coerced_to_logical <- as.logical(character_coerced_to_double)

double_coerced_to_logical

OUTPUT

[1] FALSE TRUE TRUER が基本データ型を他の型に強制する際に驚くべきことが起こる場合があります!型の強制変換の細かい点はさておき、重要なのは:データが予想していた形式と異なる場合、それは型の強制変換が原因である可能性が高いです。ベクトルやデータフレームの列内のすべてのデータが同じ型であることを確認してください。さもなければ、予想外の問題が発生する可能性があります!

しかし、強制変換は非常に便利な場合もあります!たとえば、cats

データの likes_catnip 列は数値型ですが、実際には 1 と 0

がそれぞれ TRUE と FALSE

を表しています。このデータには logical

型を使用すべきです。この型は TRUE または FALSE

の 2 状態を持ち、データの意味に完全に一致します。この列を

logical に「強制変換」するには、as.logical

関数を使用します:

R

cats$likes_catnip

OUTPUT

[1] 1 0 1R

cats$likes_catnip <- as.logical(cats$likes_catnip)

cats$likes_catnip

OUTPUT

[1] TRUE FALSE TRUEチャレンジ 1

データ分析の重要な部分は、入力データのクリーンアップです。入力データがすべて同じ形式(例:数値)であることを知っていると、分析がはるかに簡単になります!型の強制変換に関する章で扱った猫のデータセットをクリーンアップしましょう。

コードテンプレートをコピー

RStudio で新しいスクリプトを作成し、以下のコードをコピー&ペーストしてください。その後、以下のタスクを参考にギャップ(______)を埋めてください。

# データを読み込み

cats <- read.csv("data/feline-data_v2.csv")

# 1. データを表示

_____

# 2. 表の概要をデータ型と共に表示

_____(cats)

# 3. "weight" 列の現在のデータ型 __________。

# 正しいデータ型は: ____________。

# 4. 4 番目の "weight" データポイントを指定された 2 つの値の平均に修正

cats$weight[4] <- 2.35

# 効果を確認するためにデータを再表示

cats

# 5. "weight" を正しいデータ型に変換

cats$weight <- ______________(cats$weight)

# 自分でテストするために平均を計算

mean(cats$weight)

# 正しい平均値(NA ではない)が表示されたら、演習は完了です!2. データ型の概要を表示する

データ型はデータ自体と同じくらい重要です。以前見た関数を使用して、cats

テーブルのすべての列のデータ型を表示します。

3. 必要

なデータ型はどれですか?

表示されるデータ型は、このデータ(猫の体重)には適していません。必要なデータ型はどれですか?

- なぜ

read.csv()関数は正しいデータ型を選ばなかったのでしょうか? - コメントのギャップに猫の体重に適したデータ型を埋めてください!

型の階層 のセクションに戻り、利用可能なデータ型を確認してください。

4. 問題のある値を修正する

問題のある 4 行目に新しい体重値を割り当てるコードが提供されています。実行する前に考えてみてください。この例のように数値を割り当てた後のデータ型はどうなりますか? 実行後にデータ型を確認して、自分の予測が正しいか確認してください。

5. 列 “weight” を正しいデータ型に変換する

猫の体重は数値です。しかし、列にはまだ適切なデータ型が設定されていません。この列を浮動小数点数に強制変換してください。

データ型を変換する関数は as.

で始まります。このスクリプトの上部で関数を確認するか、RStudio

のオートコンプリート機能を使用してください。 “as.”

と入力し、TAB キーを押します。

チャレンジ 1.5 の解答

歴史的な理由で、2 つの同義の関数があります:

R

cats$weight <- as.double(cats$weight)

cats$weight <- as.numeric(cats$weight)

基本的なベクトル関数

c()

関数を使用すると、既存のベクトルに新しい要素を追加することができます:

R

ab_vector <- c('a', 'b')

ab_vector

OUTPUT

[1] "a" "b"R

combine_example <- c(ab_vector, 'SWC')

combine_example

OUTPUT

[1] "a" "b" "SWC"また、数列を生成することも可能です:

R

mySeries <- 1:10

mySeries

OUTPUT

[1] 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10R

seq(10)

OUTPUT

[1] 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10R

seq(1, 10, by=0.1)

OUTPUT

[1] 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 1.9 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4

[16] 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 2.9 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 3.8 3.9

[31] 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 4.8 4.9 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4

[46] 5.5 5.6 5.7 5.8 5.9 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 6.7 6.8 6.9

[61] 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 7.7 7.8 7.9 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4

[76] 8.5 8.6 8.7 8.8 8.9 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 9.6 9.7 9.8 9.9

[91] 10.0ベクトルについていくつかの質問をすることもできます:

R

sequence_example <- 20:25

head(sequence_example, n=2)

OUTPUT

[1] 20 21R

tail(sequence_example, n=4)

OUTPUT

[1] 22 23 24 25R

length(sequence_example)

OUTPUT

[1] 6R

typeof(sequence_example)

OUTPUT

[1] "integer"ベクトルの特定の要素を取得するには、角括弧記法を使用します:

R

first_element <- sequence_example[1]

first_element

OUTPUT

[1] 20特定の要素を変更するには、角括弧を矢印の右側に使用します:

R

sequence_example[1] <- 30

sequence_example

OUTPUT

[1] 30 21 22 23 24 25チャレンジ 2

1 から 26 までの数を含むベクトルを作成します。その後、このベクトルを 2 倍にします。

R

x <- 1:26

x <- x * 2

リスト

次に紹介するデータ構造は list

です。リストは他のデータ型よりもシンプルで、何でも入れることができるのが特徴です。ベクトルでは要素の基本データ型を統一する必要がありましたが、リストは異なるデータ型を持つことができます:

R

list_example <- list(1, "a", TRUE, 1+4i)

list_example

OUTPUT

[[1]]

[1] 1

[[2]]

[1] "a"

[[3]]

[1] TRUE

[[4]]

[1] 1+4istr()

を使用してオブジェクトの構造を表示すると、すべての要素のデータ型を確認できます:

R

str(list_example)

OUTPUT

List of 4

$ : num 1

$ : chr "a"

$ : logi TRUE

$ : cplx 1+4iリストの用途は何でしょうか?例えば、異なるデータ型を持つ関連データを整理できます。これは、Excel のスプレッドシートのように複数の表をまとめるのと似ています。他にも多くの用途があります。

次の章で、驚くかもしれない別の例を紹介します。

リストの特定の要素を取得するには 二重角括弧 を使用します:

R

list_example[[2]]

OUTPUT

[1] "a"リストの要素には 名前 を付けることもできます。名前を値の前に等号で指定します:

R

another_list <- list(title = "Numbers", numbers = 1:10, data = TRUE )

another_list

OUTPUT

$title

[1] "Numbers"

$numbers

[1] 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

$data

[1] TRUEこれにより 名前付きリスト が生成されます。これで新しいアクセス方法が追加されます!

R

another_list$title

OUTPUT

[1] "Numbers"名前

名前を使用すると、要素に意味を持たせることができます。これにより、データだけでなく説明情報も持つことができます。これはオブジェクトに貼り付けられるラベルのような メタデータ です。R ではこれは 属性 と呼ばれます。属性により、オブジェクトをさらに操作することが可能になります。ここでは、定義された名前で要素にアクセスすることができます。

名前を使用してベクトルやリストにアクセスする

名前付きリストの生成方法はすでに学びました。名前付きベクトルを生成する方法も非常に似ています。以前このような関数を見たことがあるはずです:

R

pizza_price <- c( pizzasubito = 5.64, pizzafresh = 6.60, callapizza = 4.50 )

しかし、要素の取得方法はリストとは異なります:

R

pizza_price["pizzasubito"]

OUTPUT

pizzasubito

5.64 リストのアプローチは機能しません:

R

pizza_price$pizzafresh

ERROR

Error in pizza_price$pizzafresh: $ operator is invalid for atomic vectorsこのエラーメッセージを覚えておくと役立ちます。同じようなエラーに遭遇することが多いですが、これはリストと勘違いしてベクトルの要素にアクセスしようとした場合に発生します。

名前の取得と変更

名前だけに興味がある場合は、names()

関数を使用します:

R

names(pizza_price)

OUTPUT

[1] "pizzasubito" "pizzafresh" "callapizza" ベクトルの要素にアクセスしたり変更したりする方法を学びました。同じことが名前についても可能です:

R

names(pizza_price)[3]

OUTPUT

[1] "callapizza"R

names(pizza_price)[3] <- "call-a-pizza"

pizza_price

OUTPUT

pizzasubito pizzafresh call-a-pizza

5.64 6.60 4.50 チャレンジ 3

-

pizza_priceの名前のデータ型は何ですか?str()またはtypeof()関数を使用して調べてください。

オブジェクトの名前を取得するには、その名前を names(...)

で囲みます。同様に、名前のデータ型を取得するには、全体をさらに

typeof(...) で囲みます:

typeof(names(pizza))または、コードをわかりやすくするために新しい変数を使用します:

n <- names(pizza)

typeof(n)チャレンジ 4

既存のベクトルやリストの一部の名前を変更する代わりに、オブジェクトのすべての名前を設定することも可能です。次のコード形式を使用します(すべての大文字部分を置き換えてください):

names( OBJECT ) <- CHARACTER_VECTORアルファベットの各文字に番号を割り当てるベクトルを作成しましょう!

- 1 から 26 の数列を持つ

letter_noというベクトルを作成します。 - R には

LETTERSという組み込みオブジェクトがあります。これは A から Z までの 26 文字を含むベクトルです。この 26 文字をletter_noの名前として設定します。 -

letter_no["B"]を呼び出して、値が 2 であることを確認してください!

letter_no <- 1:26 # or seq(1,26)

names(letter_no) <- LETTERS

letter_no["B"]データフレーム

このレッスンの冒頭でデータフレームについて簡単に触れましたが、それはデータの表形式を表しています。例として示した猫のデータフレームについては詳細に掘り下げていませんでした:

R

cats

OUTPUT

coat weight likes_catnip

1 calico 2.1 TRUE

2 black 5.0 FALSE

3 tabby 3.2 TRUEここで少し驚くべきことに気づくかもしれません。次のコマンドを実行してみましょう:

R

typeof(cats)

OUTPUT

[1] "list"データフレームが「内部的にはリストのように見える」ことがわかります。以前、リストについて次のように説明しました:

リストは異なる型のデータを整理するためのもの

データフレームの列は、それぞれが異なる型のベクトルであり、同じ表に属することで整理されています。

データフレームは実際にはベクトルのリストです。データフレームが特別なのは、すべてのベクトルが同じ長さでなければならない点です。

この「特別さ」はどのようにオブジェクトに組み込まれているのでしょうか?R がそれを単なるリストではなく、表として扱うのはなぜでしょう?

R

class(cats)

OUTPUT

[1] "data.frame"クラス は名前と同様に、オブジェクトに付加される属性です。この属性は、そのオブジェクトが人間にとって何を意味するのかを示します。

ここで疑問に思うかもしれません:なぜオブジェクトの型を判断するための関数がもう一つ必要なのでしょうか?すでに

typeof() がありますよね?typeof()

はオブジェクトがコンピュータ内でどのように構築されているかを教えてくれます。一方、class()

はオブジェクトの人間にとっての意味を示します。したがって、typeof()

の出力は R で固定されています(主に 5

種類のデータ型)が、class() の出力は R

パッケージによって多様で拡張可能です。

cats

の例では、整数型、倍精度数値型、論理型の変数が含まれています。すでに見たように、データフレームの各列はベクトルです:

R

cats$coat

OUTPUT

[1] "calico" "black" "tabby" R

cats[,1]

OUTPUT

[1] "calico" "black" "tabby" R

typeof(cats[,1])

OUTPUT

[1] "character"R

str(cats[,1])

OUTPUT

chr [1:3] "calico" "black" "tabby"一方、各行は異なる変数の観測値であり、それ自体がデータフレームであり、異なる型の要素で構成されることができます:

R

cats[1,]

OUTPUT

coat weight likes_catnip

1 calico 2.1 TRUER

typeof(cats[1,])

OUTPUT

[1] "list"R

str(cats[1,])

OUTPUT

'data.frame': 1 obs. of 3 variables:

$ coat : chr "calico"

$ weight : num 2.1

$ likes_catnip: logi TRUEチャレンジ 5

データフレームから変数、観測値、要素を取得する方法はいくつかあります:

cats[1]cats[[1]]cats$coatcats["coat"]cats[1, 1]cats[, 1]cats[1, ]

これらの例を試して、それぞれが何を返すのかを説明してください。

ヒント: 返されるものを調べるには、typeof()

関数を使用してください。

R

cats[1]

OUTPUT

coat

1 calico

2 black

3 tabbyデータフレームはベクトルのリストと考えられます。単一ブラケット

[1]

はリストの最初のスライスを別のリストとして返します。この場合、それはデータフレームの最初の列です。

R

cats[[1]]

OUTPUT

[1] "calico" "black" "tabby" 二重ブラケット [[1]]

はリスト項目の内容を返します。この場合、最初の列の内容である

character 型のベクトルです。

R

cats$coat

OUTPUT

[1] "calico" "black" "tabby" $

を使用して名前で項目にアクセスします。coat

はデータフレームの最初の列であり、character

型のベクトルです。

R

cats["coat"]

OUTPUT

coat

1 calico

2 black

3 tabby単一ブラケット ["coat"]

を使用し、インデックス番号の代わりに列名を指定します。例 1

と同様に、返されるオブジェクトは list です。

R

cats[1, 1]

OUTPUT

[1] "calico"単一ブラケットを使用し、行と列の座標を指定します。この場合、1 行目 1 列目の値が返されます。オブジェクトは character 型のベクトルです。

R

cats[, 1]

OUTPUT

[1] "calico" "black" "tabby" 前の例と同様に単一ブラケットを使用し、行と列の座標を指定しますが、行座標が指定されていません。この場合、R は欠損値をその列のすべての要素として解釈し、ベクトル として返します。

R

cats[1, ]

OUTPUT

coat weight likes_catnip

1 calico 2.1 TRUE再び単一ブラケットを使用し、行と列の座標を指定しますが、今回は列座標が指定されていません。返される値は 1 行目のすべての値を含む list です。

ヒント: データフレーム列の名前変更

データフレームには列名があり、names()

関数でアクセスできます:

R

names(cats)

OUTPUT

[1] "coat" "weight" "likes_catnip"cats の 2

番目の列の名前を変更したい場合は、names(cats) の 2

番目の要素に新しい名前を割り当てます:

R

names(cats)[2] <- "weight_kg"

cats

OUTPUT

coat weight_kg likes_catnip

1 calico 2.1 TRUE

2 black 5.0 FALSE

3 tabby 3.2 TRUE行列(Matrix)

最後に紹介するのは行列です。ゼロで満たされた行列を宣言してみましょう:

R

matrix_example <- matrix(0, ncol=6, nrow=3)

matrix_example

OUTPUT

[,1] [,2] [,3] [,4] [,5] [,6]

[1,] 0 0 0 0 0 0

[2,] 0 0 0 0 0 0

[3,] 0 0 0 0 0 0行列を特別なものにしているのは dim() 属性です:

R

dim(matrix_example)

OUTPUT

[1] 3 6他のデータ構造と同様に、行列について質問することも可能です:

R

typeof(matrix_example)

OUTPUT

[1] "double"R

class(matrix_example)

OUTPUT

[1] "matrix" "array" R

str(matrix_example)

OUTPUT

num [1:3, 1:6] 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 ...R

nrow(matrix_example)

OUTPUT

[1] 3R

ncol(matrix_example)

OUTPUT

[1] 6チャレンジ 6

次のコードの結果はどうなるでしょうか?

R

length(matrix_example)

OUTPUT

[1] 18実行して確認してください。予想は当たりましたか?なぜそのような結果になるのでしょうか?

行列は次元属性を持つベクトルであるため、length

は行列内の要素の総数を返します:

R

matrix_example <- matrix(0, ncol=6, nrow=3)

length(matrix_example)

OUTPUT

[1] 18チャレンジ 7

1 から 50 の数値を含む、列数 5、行数 10 の行列を作成します。

デフォルトの動作として、この行列は列ごとに値が埋められますか、それとも行ごとですか?

その動作を変更する方法を調べてください。(ヒント:matrix

のドキュメントを参照)

R

x <- matrix(1:50, ncol=5, nrow=10)

x <- matrix(1:50, ncol=5, nrow=10, byrow = TRUE) # 行ごとに埋める

チャレンジ 8

このワークショップの次のセクションに対応する 2 つの要素を持つリストを作成します:

- データ型

- データ構造

各データ型およびデータ構造の名前を文字型ベクトルに格納してください。

R

dataTypes <- c('double', 'complex', 'integer', 'character', 'logical')

dataStructures <- c('data.frame', 'vector', 'list', 'matrix')

answer <- list(dataTypes, dataStructures)

チャレンジ 9

以下の行列の R 出力を考えてみてください:

OUTPUT

[,1] [,2]

[1,] 4 1

[2,] 9 5

[3,] 10 7この行列を作成するために使用された正しいコマンドはどれでしょうか?各コマンドを確認し、入力する前に正しいものを考えてください。

他のコマンドでどのような行列が作成されるかを考えてみてください。

matrix(c(4, 1, 9, 5, 10, 7), nrow = 3)matrix(c(4, 9, 10, 1, 5, 7), ncol = 2, byrow = TRUE)matrix(c(4, 9, 10, 1, 5, 7), nrow = 2)matrix(c(4, 1, 9, 5, 10, 7), ncol = 2, byrow = TRUE)

R

matrix(c(4, 1, 9, 5, 10, 7), ncol = 2, byrow = TRUE)

-

read.csvを使用して R で表形式データを読み取ります。 - R の基本データ型は、double、integer、complex、logical、character です。

- データフレームや行列のようなデータ構造は、リストやベクトルを基にし、いくつかの属性が追加されています。

Content from データフレームの操作

Last updated on 2025-11-11 | Edit this page

Overview

Questions

- データフレームをどのように操作できますか?

Objectives

- 行や列を追加または削除する。

- 2 つのデータフレームを結合する。

- データフレームのサイズ、列のクラス、名前、最初の数行などの基本的なプロパティを表示する。

これまでに、R の基本的なデータ型とデータ構造について学びました。以降の作業は、それらのツールを操作することに集約されます。最も頻繁に登場するのは、CSV ファイルから情報を読み込んで作成するデータフレームです。このレッスンでは、データフレームの操作についてさらに学びます。

データフレームに列や行を追加する

データフレームの列はベクトルであるため、列全体でデータ型が一貫しています。そのため、新しい列を追加したい場合は、まず新しいベクトルを作成します:

R

age <- c(2, 3, 5)

cats

OUTPUT

coat weight likes_catnip

1 calico 2.1 1

2 black 5.0 0

3 tabby 3.2 1これを列として追加するには、次のようにします:

R

cbind(cats, age)

OUTPUT

coat weight likes_catnip age

1 calico 2.1 1 2

2 black 5.0 0 3

3 tabby 3.2 1 5ただし、データフレームの行数と異なる要素数を持つベクトルを追加しようとすると失敗します:

R

age <- c(2, 3, 5, 12)

cbind(cats, age)

ERROR

Error in data.frame(..., check.names = FALSE): arguments imply differing number of rows: 3, 4R

age <- c(2, 3)

cbind(cats, age)

ERROR

Error in data.frame(..., check.names = FALSE): arguments imply differing number of rows: 3, 2なぜ失敗するのでしょうか?R は、新しい列の各行に 1 つの要素が必要だと考えています:

R

nrow(cats)

OUTPUT

[1] 3R

length(age)

OUTPUT

[1] 2したがって、nrow(cats) と length(age)

が等しい必要があります。新しいデータフレームを作成して、cats

に上書きしてみましょう。

R

age <- c(2, 3, 5)

cats <- cbind(cats, age)

次に、行を追加してみましょう。データフレームの行はリストであることを既に学びました:

R

newRow <- list("tortoiseshell", 3.3, TRUE, 9)

cats <- rbind(cats, newRow)

新しい行が正しく追加されたことを確認します。

R

cats

OUTPUT

coat weight likes_catnip age

1 calico 2.1 1 2

2 black 5.0 0 3

3 tabby 3.2 1 5

4 tortoiseshell 3.3 1 9行を削除する

データフレームに行や列を追加する方法を学びました。次に、行を削除する方法を見てみましょう。

R

cats

OUTPUT

coat weight likes_catnip age

1 calico 2.1 1 2

2 black 5.0 0 3

3 tabby 3.2 1 5

4 tortoiseshell 3.3 1 9最後の行を削除したデータフレームを取得するには:

R

cats[-4, ]

OUTPUT

coat weight likes_catnip age

1 calico 2.1 1 2

2 black 5.0 0 3

3 tabby 3.2 1 5コンマの後に何も指定しないことで、4 行目全体を削除することを示します。

複数の行を削除することもできます。たとえば、次のようにベクトル内に行番号を指定します:cats[c(-3,-4), ]

列を削除する

データフレームの列を削除することもできます。「age」列を削除する場合、変数番号またはインデックスを使用する方法があります。

R

cats[,-4]

OUTPUT

coat weight likes_catnip

1 calico 2.1 1

2 black 5.0 0

3 tabby 3.2 1

4 tortoiseshell 3.3 1コンマの前に何も指定しないことで、すべての行を保持することを示します。

または、インデックス名と %in%

演算子を使用して列を削除することもできます。%in%

演算子は、左側の引数(ここでは cats

の名前)の各要素について「この要素は右側の引数に含まれますか?」と尋ねます。

R

drop <- names(cats) %in% c("age")

cats[,!drop]

OUTPUT

coat weight likes_catnip

1 calico 2.1 1

2 black 5.0 0

3 tabby 3.2 1

4 tortoiseshell 3.3 1論理演算子(%in%

など)による部分集合化については、次のエピソードで詳しく説明します。詳細は

論理演算を使用した部分集合化

を参照してください。

データフレームの結合

データフレームにデータを追加する際に覚えておくべき重要な点は、列はベクトル、行はリストであることです。2

つのデータフレームを rbind

を使用して結合することもできます:

R

cats <- rbind(cats, cats)

cats

OUTPUT

coat weight likes_catnip age

1 calico 2.1 1 2

2 black 5.0 0 3

3 tabby 3.2 1 5

4 tortoiseshell 3.3 1 9

5 calico 2.1 1 2

6 black 5.0 0 3

7 tabby 3.2 1 5

8 tortoiseshell 3.3 1 9チャレンジ 1

次の構文を使用して、新しいデータフレームを R 内で作成できます:

R

df <- data.frame(id = c("a", "b", "c"),

x = 1:3,

y = c(TRUE, TRUE, FALSE))

以下の情報を持つデータフレームを作成してください:

- 名

- 姓

- ラッキーナンバー

次に、rbind

を使用して隣の人のエントリを追加します。最後に、cbind

を使用して「コーヒーブレイクの時間ですか?」という質問への各人の回答を含む列を追加してください。

R

df <- data.frame(first = c("Grace"),

last = c("Hopper"),

lucky_number = c(0))

df <- rbind(df, list("Marie", "Curie", 238) )

df <- cbind(df, coffeetime = c(TRUE, TRUE))

実用的な例

これまで、猫データを使ってデータフレーム操作の基本を学びました。次に、これらのスキルを使用して、より現実的なデータセットを扱います。以前ダウンロードした

gapminder データセットを読み込んでみましょう:

R

gapminder <- read.csv("data/gapminder_data.csv")

その他のヒント

タブ区切り値ファイル(.tsv)を扱う場合は、区切り文字として

"\\t"を指定するか、read.delim()を使用します。ファイルをインターネットから直接ダウンロードしてコンピュータの指定したローカルフォルダに保存するには、

download.file関数を使用できます。保存されたファイルをread.csv関数で読み込む例:

R

download.file("https://raw.githubusercontent.com/swcarpentry/r-novice-gapminder/main/episodes/data/gapminder_data.csv", destfile = "data/gapminder_data.csv")

gapminder <- read.csv("data/gapminder_data.csv")

- また、ファイルパスの代わりに Web アドレスを

read.csvに指定して、ファイルを直接 R に読み込むこともできます。この場合、ローカルにファイルを保存する必要はありません。例:

R

gapminder <- read.csv("https://raw.githubusercontent.com/swcarpentry/r-novice-gapminder/main/episodes/data/gapminder_data.csv")

readxl パッケージ を使用すると、Excel スプレッドシートをプレーンテキストに変換せずに直接読み込むことができます。

"stringsAsFactors"引数を使用すると、文字列を因子として読み込むか文字列として読み込むかを指定できます。R バージョン 4.0 以降では、デフォルトで文字列は文字型として読み込まれますが、古いバージョンでは因子として読み込まれるのがデフォルトでした。詳細は前のエピソードのコールアウトを参照してください。

gapminder

データセットを調べてみましょう。最初に行うべきことは、str

を使用してデータの構造を確認することです:

R

str(gapminder)

OUTPUT

'data.frame': 1704 obs. of 6 variables:

$ country : chr "Afghanistan" "Afghanistan" "Afghanistan" "Afghanistan" ...

$ year : int 1952 1957 1962 1967 1972 1977 1982 1987 1992 1997 ...

$ pop : num 8425333 9240934 10267083 11537966 13079460 ...

$ continent: chr "Asia" "Asia" "Asia" "Asia" ...

$ lifeExp : num 28.8 30.3 32 34 36.1 ...

$ gdpPercap: num 779 821 853 836 740 ...gapminder

の構造を調べる別の方法として、summary

関数を使用します。この関数は R

のさまざまなオブジェクトで使用できます。データフレームの場合、summary

は各列の数値的、表形式、または記述的な概要を提供します。数値または整数型の列は記述統計(四分位数や平均値)で、文字列型の列はその長さ、クラス、モードで説明されます。

R

summary(gapminder)

OUTPUT

country year pop continent

Length:1704 Min. :1952 Min. :6.001e+04 Length:1704

Class :character 1st Qu.:1966 1st Qu.:2.794e+06 Class :character

Mode :character Median :1980 Median :7.024e+06 Mode :character

Mean :1980 Mean :2.960e+07

3rd Qu.:1993 3rd Qu.:1.959e+07

Max. :2007 Max. :1.319e+09

lifeExp gdpPercap

Min. :23.60 Min. : 241.2

1st Qu.:48.20 1st Qu.: 1202.1

Median :60.71 Median : 3531.8

Mean :59.47 Mean : 7215.3

3rd Qu.:70.85 3rd Qu.: 9325.5

Max. :82.60 Max. :113523.1 str や summary

関数と合わせて、typeof

関数を使ってデータフレームの個々の列を調べることもできます:

R

typeof(gapminder$year)

OUTPUT

[1] "integer"R

typeof(gapminder$country)

OUTPUT

[1] "character"R

str(gapminder$country)

OUTPUT

chr [1:1704] "Afghanistan" "Afghanistan" "Afghanistan" "Afghanistan" ...データフレームの次元に関する情報も調べることができます。str(gapminder) の出力によると、gapminder には

6 つの変数の 1704

個の観測値があります。このことを覚えた上で、次のコードが何を返すか考えてみてください:

R

length(gapminder)

OUTPUT

[1] 6データフレームの長さが行数(1704)であると考えるのが妥当ですが、実際にはそうではありません。データフレームはベクトルや因子のリストで構成されていることを思い出してください:

R

typeof(gapminder)

OUTPUT

[1] "list"length が 6 を返した理由は、gapminder が 6

列のリストで構築されているためです。データセットの行数と列数を取得するには次のようにします:

R

nrow(gapminder)

OUTPUT

[1] 1704R

ncol(gapminder)

OUTPUT

[1] 6あるいは、両方を一度に取得するには:

R

dim(gapminder)

OUTPUT

[1] 1704 6すべての列のタイトルを調べることもできます。後でアクセスする際に便利です:

R

colnames(gapminder)

OUTPUT

[1] "country" "year" "pop" "continent" "lifeExp" "gdpPercap"ここで、R が報告する構造が自分の直感や予想と一致しているかどうかを確認することが重要です。各列のデータ型が妥当かどうかを確認してください。そうでない場合は、これまで学んだ R のデータ解釈の仕組みや、一貫性の重要性に基づいて問題を解決する必要があります。

データ型や構造が合理的であることを確認したら、データの探索を開始しましょう。最初の数行を確認します:

R

head(gapminder)

OUTPUT

country year pop continent lifeExp gdpPercap

1 Afghanistan 1952 8425333 Asia 28.801 779.4453

2 Afghanistan 1957 9240934 Asia 30.332 820.8530

3 Afghanistan 1962 10267083 Asia 31.997 853.1007

4 Afghanistan 1967 11537966 Asia 34.020 836.1971

5 Afghanistan 1972 13079460 Asia 36.088 739.9811

6 Afghanistan 1977 14880372 Asia 38.438 786.1134チャレンジ 2

データの最後の数行や中間のいくつかの行も確認するのが良い習慣です。これをどのように行いますか?

特に中間の行を探すのは難しくありませんが、ランダムな行をいくつか取得することもできます。これをどのようにコード化しますか?

最後の数行を確認するには、R に既にある関数を使用すれば簡単です:

R

tail(gapminder)

tail(gapminder, n = 15)

では、途中の任意の行を確認するにはどうすればよいでしょうか?

再現性のある分析を確保するために、コードをスクリプトファイルに保存し、後で再利用できるようにしましょう。

チャレンジ 3

File -> New File -> R Script に移動し、gapminder

データセットを読み込むための R スクリプトを作成します。このスクリプトを

scripts/

ディレクトリに保存し、バージョン管理に追加してください。

その後、source

関数を使用してスクリプトを実行します。ファイルパスを引数として指定するか、RStudio

の「Source」ボタンを押します。

source

関数はスクリプト内で別のスクリプトを使用するために使用できます。同じ種類のファイルを何度も読み込む必要がある場合、一度スクリプトとして保存すれば、以降はそれを繰り返し利用できます。

R

download.file("https://raw.githubusercontent.com/swcarpentry/r-novice-gapminder/main/episodes/data/gapminder_data.csv", destfile = "data/gapminder_data.csv")

gapminder <- read.csv(file = "data/gapminder_data.csv")

データを gapminder

変数に読み込むには次のようにします:

R

source(file = "scripts/load-gapminder.R")

チャレンジ 4

str(gapminder)

の出力をもう一度読み、リストやベクトルについて学んだこと、および

colnames や dim

の出力を活用して、str

が表示する内容を説明してください。理解できない部分があれば、隣の人と相談してみてください。

オブジェクト gapminder

はデータフレームで、列は次のようになっています:

-

countryとcontinentは文字列(character)。 -

yearは整数型のベクトル。 -

pop、lifeExp、gdpPercapは数値型のベクトル。

- 新しい列をデータフレームに追加するには

cbind()を使用します。 - 新しい行をデータフレームに追加するには

rbind()を使用します。 - データフレームから行を削除します。

- データフレームの構造を理解するために、

str()、summary()、nrow()、ncol()、dim()、colnames()、head()、typeof()を使用します。 -

read.csv()を使用して CSV ファイルを読み込みます。 - データフレームの

length()が何を表しているのか理解します。

Content from データの部分集合化

Last updated on 2025-11-11 | Edit this page

Overview

Questions

- R でデータの部分集合をどのように扱うことができますか?

Objectives

- ベクトル、因子、行列、リスト、データフレームの部分集合化を学ぶ

- インデックス、名前、比較演算を使って個々の要素や複数の要素を抽出する方法を理解する

- さまざまなデータ構造から要素をスキップまたは削除する方法を習得する

R には強力な部分集合化のための演算子が数多く用意されています。それらを習得することで、あらゆる種類のデータセットで複雑な操作を簡単に行えるようになります。

あらゆる種類のオブジェクトを部分集合化するために 6 つの異なる方法があり、データ構造ごとに 3 種類の部分集合化演算子があります。

では、R の基本となる数値ベクトルを使って始めましょう。

R

x <- c(5.4, 6.2, 7.1, 4.8, 7.5)

names(x) <- c('a', 'b', 'c', 'd', 'e')

x

OUTPUT

a b c d e

5.4 6.2 7.1 4.8 7.5 アトミックベクトル

R では、文字列、数値、または論理値を含む単純なベクトルを アトミックベクトル と呼びます。これは、さらに単純化できないためです。

このようにダミーベクトルを作成しました。この中身をどのように取得するのでしょうか?

インデックスを使用した要素のアクセス

ベクトルの要素を抽出するには、対応するインデックスを指定します(1 から始まります):

R

x[1]

OUTPUT

a

5.4 R

x[4]

OUTPUT

d

4.8 角括弧 [] 演算子は関数であり、ベクトルや行列に対して「n

番目の要素を取得する」という意味を持ちます。

複数の要素を一度に取得することもできます:

R

x[c(1, 3)]

OUTPUT

a c

5.4 7.1 またはベクトルの一部(スライス)を取得することも可能です:

R

x[1:4]

OUTPUT

a b c d

5.4 6.2 7.1 4.8 :

演算子は左の値から右の値までの数値のシーケンスを生成します。

R

1:4

OUTPUT

[1] 1 2 3 4R

c(1, 2, 3, 4)

OUTPUT

[1] 1 2 3 4同じ要素を複数回取得することもできます:

R

x[c(1,1,3)]

OUTPUT

a a c

5.4 5.4 7.1 ベクトルの長さを超えるインデックスを指定すると、R は欠損値を返します:

R

x[6]

OUTPUT

<NA>

NA これは NA を含む長さ 1 のベクトルであり、名前も

NA です。

0 番目の要素を要求すると、空のベクトルが返されます:

R

x[0]

OUTPUT

named numeric(0)R のベクトルの番号付けは 1 から始まる

多くのプログラミング言語(C や Python など)では、ベクトルの最初の要素のインデックスは 0 です。一方、R では最初の要素は 1 です。

要素のスキップと削除

ベクトルのインデックスに負の数を使用すると、指定した要素を除くすべての要素が返されます:

R

x[-2]

OUTPUT

a c d e

5.4 7.1 4.8 7.5 複数の要素をスキップすることも可能です:

R

x[c(-1, -5)] # または x[-c(1,5)]

OUTPUT

b c d

6.2 7.1 4.8 ヒント: 演算の順序

ベクトルの一部をスキップしようとすると、新しい人はよく間違えます。例えば:

R

x[-1:3]

このコードは次のようなエラーを返します:

ERROR

Error in x[-1:3]: only 0's may be mixed with negative subscriptsこれは演算の順序が関係しています。:

は実際には関数であり、最初の引数を -1、2 番目の引数を

3

としてシーケンスを生成します:c(-1, 0, 1, 2, 3)。

正しい解決策は、この関数呼び出しを括弧で囲み、-

演算子を結果に適用することです:

R

x[-(1:3)]

OUTPUT

d e

4.8 7.5 ベクトルから要素を削除するには、結果を変数に再割り当てする必要があります:

R

x <- x[-4]

x

OUTPUT

a b c e

5.4 6.2 7.1 7.5 チャレンジ 1

次のコードが与えられた場合:

R

x <- c(5.4, 6.2, 7.1, 4.8, 7.5)

names(x) <- c('a', 'b', 'c', 'd', 'e')

print(x)

OUTPUT

a b c d e

5.4 6.2 7.1 4.8 7.5 次の出力を生成する少なくとも 2 つの異なるコマンドを考え出してください:

OUTPUT

b c d

6.2 7.1 4.8 2 つの異なるコマンドを見つけたら、隣の人と比較してみてください。異なる戦略を持っていましたか?

R

x[2:4]

OUTPUT

b c d

6.2 7.1 4.8 R

x[-c(1,5)]

OUTPUT

b c d

6.2 7.1 4.8 R

x[c(2,3,4)]

OUTPUT

b c d

6.2 7.1 4.8 名前によるサブセット

インデックスではなく名前を使って要素を抽出することができます:

R

x <- c(a=5.4, b=6.2, c=7.1, d=4.8, e=7.5) # ベクトルにその場で名前を付ける

x[c("a", "c")]

OUTPUT

a c

5.4 7.1 これは、オブジェクトをサブセットする際に、通常より信頼性の高い方法です。

サブセット操作を連続して行う場合、要素の位置が変わることがありますが、名前は常に変わりません!

他の論理演算を用いたサブセット

論理ベクトルを使ってサブセットを取ることもできます:

R

x[c(FALSE, FALSE, TRUE, FALSE, TRUE)]

OUTPUT

c e

7.1 7.5 比較演算子(例:>、<、==)は論理ベクトルを生成するため、それを使ってベクトルを簡潔にサブセットできます。以下のステートメントは、前の例と同じ結果を返します。

R

x[x > 7]

OUTPUT

c e

7.1 7.5 このステートメントを分解すると、まず x>7

が評価されて論理ベクトル c(FALSE, FALSE, TRUE, FALSE, TRUE)

が生成され、それに基づいて x の要素が選択されます。

名前によるインデックス操作を模倣するには、==

を使うことができます(比較には = ではなく ==

を使用する必要がある点に注意):

R

x[names(x) == "a"]

OUTPUT

a

5.4 ヒント: 複数の論理条件の結合

複数の論理条件を結合したい場合があります。たとえば、特定の範囲内の寿命を持つアジアまたはヨーロッパに位置するすべての国を見つけたいとします。このような場合、R では論理ベクトルを結合するための以下の演算子を使用できます:

-

&(論理AND): 左右がともにTRUEの場合にTRUEを返します。 -

|(論理OR): 左右のいずれか、または両方がTRUEの場合にTRUEを返します。

& や | の代わりに

&& や ||

が使われることもありますが、これらはベクトルの最初の要素だけを見て残りを無視します。データ解析では、通常1文字の演算子(&

や

|)を使用し、2文字の演算子はプログラミング(ステートメントの実行を決定する際など)で使用してください。

-

!(論理NOT):TRUEをFALSEに、FALSEをTRUEに変換します。単一の条件(例:!TRUEはFALSEになる)や、ベクトル全体(例:!c(TRUE, FALSE)はc(FALSE, TRUE)になる)を否定できます。

また、単一のベクトル内の要素を比較するために、all(すべての要素が

TRUE の場合に TRUE を返す)や

any(1つ以上の要素が TRUE の場合に

TRUE を返す)関数を使用できます。

チャレンジ 2

以下のコードを用いて:

R

x <- c(5.4, 6.2, 7.1, 4.8, 7.5)

names(x) <- c('a', 'b', 'c', 'd', 'e')

print(x)

OUTPUT

a b c d e

5.4 6.2 7.1 4.8 7.5 x から 4 より大きく 7

未満の値を返すサブセットコマンドを書いてください。

R

x_subset <- x[x<7 & x>4]

print(x_subset)

OUTPUT

a b d

5.4 6.2 4.8 ヒント: 重複する名前

1つのベクトル内で複数の要素が同じ名前を持つことも可能です(データフレームでは、列名が重複することはありますが、行名は一意である必要があります)。以下の例を考えてみてください:

R

x <- 1:3

x

OUTPUT

[1] 1 2 3R

names(x) <- c('a', 'a', 'a')

x

OUTPUT

a a a

1 2 3 R

x['a'] # 最初の値のみを返す

OUTPUT

a

1 R

x[names(x) == 'a'] # すべての値を返す

OUTPUT

a a a

1 2 3 ヒント: 演算子に関するヘルプを得る方法

演算子を引用符で囲むことで、ヘルプを検索できます:help("%in%") または ?"%in%"。

名前付き要素をスキップする

名前付き要素をスキップまたは削除するのは少し難しいです。文字列を否定してスキップしようとすると、R は「文字列を否定する方法が分からない」というやや分かりにくいエラーを出します:

R

x <- c(a=5.4, b=6.2, c=7.1, d=4.8, e=7.5) # もう一度その場でベクトルに名前を付ける

x[-"a"]

ERROR

Error in -"a": invalid argument to unary operatorしかし、!=(等しくない)演算子を使用して論理ベクトルを構築すれば、望む動作を実現できます:

R

x[names(x) != "a"]

OUTPUT

b c d e

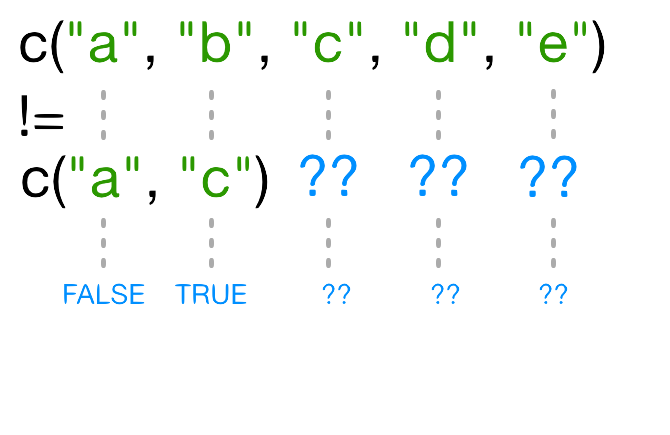

6.2 7.1 4.8 7.5 複数の名前付きインデックスをスキップするのはさらに難しいです。例えば、"a"

と "c" を削除しようとして次のように試みます:

R

x[names(x)!=c("a","c")]

WARNING

Warning in names(x) != c("a", "c"): longer object length is not a multiple of

shorter object lengthOUTPUT

b c d e

6.2 7.1 4.8 7.5 R は 何か をしましたが、警告を出しており、それが示す通り

間違った結果 を返しました("c"

要素がまだベクトルに含まれています)。

!=

がこの場合に何を実際にしているのかは、非常に良い質問です。

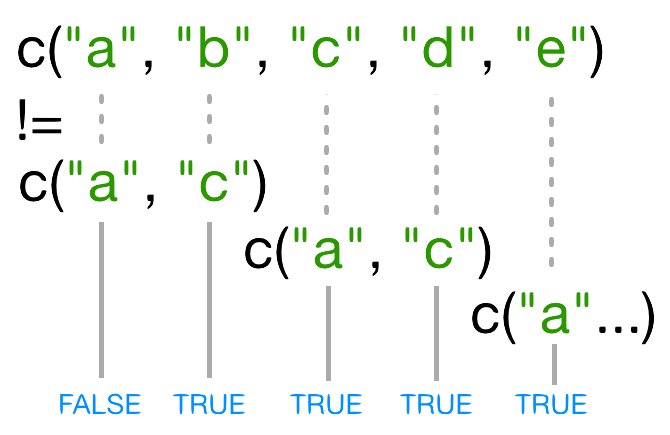

リサイクル

このコードの比較部分を見てみましょう:

R

names(x) != c("a", "c")

WARNING

Warning in names(x) != c("a", "c"): longer object length is not a multiple of

shorter object lengthOUTPUT

[1] FALSE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUEnames(x)[3] != "c" は明らかに偽なのに、なぜ R

はこのベクトルの3番目の要素に TRUE

を返すのでしょうか?!= を使用すると、R

は左辺の各要素を右辺の対応する要素と比較しようとします。左辺と右辺の長さが異なる場合はどうなりますか?

一方のベクトルがもう一方より短い場合、短いベクトルは リサイクル されます:

この場合、R は c("a", "c") を必要な回数だけ繰り返して

names(x)

と一致させます(例:c("a","c","a","c","a"))。

再利用された "a" が names(x)

の3番目の要素と一致しないため、!= の結果が

TRUE になります。

リサイクルによりこのような間違いが発生するのを防ぐには

%in%

演算子を使用します。この演算子は左辺の各要素について、右辺の中にその要素が存在するかどうかを確認します。今回は値を除外したいので、!

演算子も使用します:

R

x[! names(x) %in% c("a","c") ]

OUTPUT

b d e

6.2 4.8 7.5 チャレンジ 3

ベクトルの要素を、特定のリスト内のいずれかと一致させる操作は、データ解析で非常に一般的なタスクです。例えば、gapminder

データセットには country と continent

の変数がありますが、これらの間の情報は含まれていません。東南アジアの情報を抽出したいとします。このとき、どのようにして東南アジアのすべての国について

TRUE、それ以外を FALSE

とする論理ベクトルを作成しますか?

以下のデータを使用します:

R

seAsia <- c("Myanmar","Thailand","Cambodia","Vietnam","Laos")

## エピソード2でダウンロードした gapminder データを読み込む

gapminder <- read.csv("data/gapminder_data.csv", header=TRUE)

## データフレームから `country` 列を抽出(詳細は後述);

## factor を文字列に変換;

## 重複しない要素のみ取得

countries <- unique(as.character(gapminder$country))

以下の3つの方法を試し、それぞれがどのように(正しくない、または正しい方法で)動作するのか説明してください:

-

間違った方法(

==のみを使用)

-

不格好な方法(論理演算子

==と|を使用)

-

エレガントな方法(

%in%を使用)

間違った方法

countries==seAsia

この方法では、警告("In countries == seAsia : 長いオブジェクトの長さが短いオブジェクトの長さの倍数ではありません")が表示され、誤った結果(すべてFALSEのベクトル)が返されます。これは、seAsiaの再利用された値が正しい位置に一致しないためです。不格好な方法

以下のコードでは正しい値を得ることができますが、非常に冗長で扱いにくいです:

R

(countries=="Myanmar" | countries=="Thailand" |

countries=="Cambodia" | countries == "Vietnam" | countries=="Laos")

または、countries==seAsia[1] | countries==seAsia[2] | ...

のように記述します。

リストが長い場合、さらに複雑になります。

-

エレガントな方法

countries %in% seAsia

この方法は正確で、記述が簡単で可読性も高いです。

特殊値の扱い

R

では、欠損値、無限値、未定義値を処理できない関数に出会うことがあります。

そのようなデータをフィルタリングするために、以下の特殊な関数を使用できます:

-

is.na:ベクトル、行列、またはデータフレーム内のNA(またはNaN)を含む位置を返します。 - 同様に、

is.nanとis.infiniteは、それぞれNaNとInfに対応します。 -

is.finite:NA、NaN、Infを含まない位置を返します。 -

na.omit:ベクトルからすべての欠損値を除外します。

因子のサブセット

ベクトルのサブセット方法を学んだところで、他のデータ構造のサブセットについて考えてみましょう。

因子のサブセットは、ベクトルのサブセットと同じ方法で行えます。

R

f <- factor(c("a", "a", "b", "c", "c", "d"))

f[f == "a"]

OUTPUT

[1] a a

Levels: a b c dR

f[f %in% c("b", "c")]

OUTPUT

[1] b c c

Levels: a b c dR

f[1:3]

OUTPUT

[1] a a b

Levels: a b c d要素をスキップしても、そのカテゴリが因子レベルから削除されるわけではありません:

R

f[-3]

OUTPUT

[1] a a c c d

Levels: a b c d行列のサブセット

行列は [

関数を使用してサブセットします。この場合、2つの引数を取り、1つ目は行、2つ目は列に適用されます:

R

set.seed(1)

m <- matrix(rnorm(6*4), ncol=4, nrow=6)

m[3:4, c(3,1)]

OUTPUT

[,1] [,2]

[1,] 1.12493092 -0.8356286

[2,] -0.04493361 1.5952808行または列全体を取得する場合は、1つ目または2つ目の引数を空白のままにします:

R

m[, c(3,4)]

OUTPUT

[,1] [,2]

[1,] -0.62124058 0.82122120

[2,] -2.21469989 0.59390132

[3,] 1.12493092 0.91897737

[4,] -0.04493361 0.78213630

[5,] -0.01619026 0.07456498

[6,] 0.94383621 -1.989351701つの行または列のみを取得すると、結果が自動的にベクトルに変換されます:

R

m[3,]

OUTPUT

[1] -0.8356286 0.5757814 1.1249309 0.9189774結果を行列として保持するには、第3引数 を指定して

drop = FALSE を設定します:

R

m[3, , drop=FALSE]

OUTPUT

[,1] [,2] [,3] [,4]

[1,] -0.8356286 0.5757814 1.124931 0.9189774行または列の外側をアクセスしようとすると、R はエラーをスローします:

R

m[, c(3,6)]

ERROR

Error in m[, c(3, 6)]: subscript out of boundsヒント: 高次元配列

多次元配列の場合、[

の各引数が次元に対応します。例えば、3次元配列の場合、最初の3つの引数が行、列、および深さ次元に対応します。

行列はベクトルであるため、1つの引数だけを使用してサブセットを取ることもできます:

R

m[5]

OUTPUT

[1] 0.3295078これは通常あまり有用ではなく、読み取りづらい場合があります。ただし、行列がデフォルトで 列優先フォーマット に配置されていることを理解するのに役立ちます。つまり、ベクトルの要素は列ごとに配置されます:

R

matrix(1:6, nrow=2, ncol=3)

OUTPUT

[,1] [,2] [,3]

[1,] 1 3 5

[2,] 2 4 6行ごとに行列を埋めたい場合は、byrow=TRUE

を使用します:

R

matrix(1:6, nrow=2, ncol=3, byrow=TRUE)

OUTPUT

[,1] [,2] [,3]

[1,] 1 2 3

[2,] 4 5 6行列は、行および列のインデックスの代わりに、その行名および列名を使用してサブセットを取ることもできます。

チャレンジ 4

以下のコードを用いて:

R

m <- matrix(1:18, nrow=3, ncol=6)

print(m)

OUTPUT

[,1] [,2] [,3] [,4] [,5] [,6]

[1,] 1 4 7 10 13 16

[2,] 2 5 8 11 14 17

[3,] 3 6 9 12 15 18- 以下のコマンドのうち、11 と 14 を抽出するものはどれでしょうか?

A. m[2,4,2,5]

B. m[2:5]

C. m[4:5,2]

D. m[2,c(4,5)]

D

リストのサブセット

ここでは新しいサブセット演算子を紹介します。リストをサブセットするためには、3つの関数を使用します。これらは、原子ベクトルや行列を学ぶ際にも登場しました:[,

[[, $ です。

[

を使用すると、常にリストが返されます。リストから要素を「抽出」するのではなく「サブセット」したい場合に使用します。

R

xlist <- list(a = "Software Carpentry", b = 1:10, data = head(mtcars))

xlist[1]

OUTPUT

$a

[1] "Software Carpentry"このコードは、1つの要素を含むリスト を返します。

リストの要素は、原子ベクトルと同じ方法でサブセットできます。ただし、比較演算は再帰的ではなく、リスト内のデータ構造に基づいて条件が評価されるため、リスト内の個々の要素には適用されません。

R

xlist[1:2]

OUTPUT

$a

[1] "Software Carpentry"

$b

[1] 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10リストの個々の要素を抽出するには、二重角括弧関数 [[

を使用する必要があります。

R

xlist[[1]]

OUTPUT

[1] "Software Carpentry"この結果はリストではなくベクトルであることに注意してください。

複数の要素を一度に抽出することはできません:

R

xlist[[1:2]]

ERROR

Error in xlist[[1:2]]: subscript out of boundsまた、要素をスキップすることもできません:

R

xlist[[-1]]

ERROR

Error in xlist[[-1]]: invalid negative subscript in get1index <real>ただし、名前を使用して要素をサブセットおよび抽出することは可能です:

R

xlist[["a"]]

OUTPUT

[1] "Software Carpentry"$

演算子は、名前で要素を抽出するための簡潔な記法を提供します:

R

xlist$data

OUTPUT

mpg cyl disp hp drat wt qsec vs am gear carb

Mazda RX4 21.0 6 160 110 3.90 2.620 16.46 0 1 4 4

Mazda RX4 Wag 21.0 6 160 110 3.90 2.875 17.02 0 1 4 4

Datsun 710 22.8 4 108 93 3.85 2.320 18.61 1 1 4 1

Hornet 4 Drive 21.4 6 258 110 3.08 3.215 19.44 1 0 3 1

Hornet Sportabout 18.7 8 360 175 3.15 3.440 17.02 0 0 3 2

Valiant 18.1 6 225 105 2.76 3.460 20.22 1 0 3 1チャレンジ 5

以下のリストが与えられています:

R

xlist <- list(a = "Software Carpentry", b = 1:10, data = head(mtcars))

リストとベクトルのサブセット方法を用いて、xlist

から数字の 2 を抽出してください。

ヒント:数字の 2 はリスト内の "b" に含まれています。

R

xlist$b[2]

OUTPUT

[1] 2R

xlist[[2]][2]

OUTPUT

[1] 2R

xlist[["b"]][2]

OUTPUT

[1] 2チャレンジ 6

以下の線形モデルが与えられています:

R

mod <- aov(pop ~ lifeExp, data=gapminder)

残差の自由度を抽出してください(ヒント:attributes()

が役立ちます)。

R

attributes(mod) ## `df.residual` は `mod` の名前の1つです

R

mod$df.residual

データフレーム

データフレームは内部的にはリストであることを覚えておきましょう。そのため、同様のルールが適用されます。ただし、データフレームは2次元のオブジェクトでもあります:

[

に1つの引数を与える場合、リストと同様に動作し、それぞれのリスト要素が列に対応します。結果として得られるオブジェクトはデータフレームになります:

R

head(gapminder[3])

OUTPUT

pop

1 8425333

2 9240934

3 10267083

4 11537966

5 13079460

6 14880372同様に、[[ を使用すると、単一の列

を抽出します:

R

head(gapminder[["lifeExp"]])

OUTPUT

[1] 28.801 30.332 31.997 34.020 36.088 38.438$

演算子は、列を名前で抽出するための便利なショートカットを提供します:

R

head(gapminder$year)

OUTPUT

[1] 1952 1957 1962 1967 1972 19772つの引数を与えると、[

は行列と同じように動作します:

R

gapminder[1:3,]

OUTPUT

country year pop continent lifeExp gdpPercap

1 Afghanistan 1952 8425333 Asia 28.801 779.4453

2 Afghanistan 1957 9240934 Asia 30.332 820.8530

3 Afghanistan 1962 10267083 Asia 31.997 853.1007単一行をサブセットすると、結果はデータフレームになります(要素が混合型のためです):

R

gapminder[3,]

OUTPUT

country year pop continent lifeExp gdpPercap

3 Afghanistan 1962 10267083 Asia 31.997 853.1007ただし、単一列をサブセットすると結果はベクトルになります(第3引数

drop = FALSE を指定することで変更可能)。

チャレンジ 7

以下の一般的なデータフレームサブセットエラーを修正してください:

- 年 1957 の観測値を抽出する

- 1列目から4列目以外のすべての列を抽出する

R

gapminder[,-1:4]

- 寿命が80年以上の行を抽出する

R

gapminder[gapminder$lifeExp > 80]

- 1行目と4列目、5列目(

continentとlifeExp)を抽出する

R

gapminder[1, 4, 5]

- 応用:年 2002 年と 2007 年の情報を含む行を抽出する

R

gapminder[gapminder$year == 2002 | 2007,]

以下の一般的なデータフレームサブセットエラーを修正:

- 年 1957 の観測値を抽出する

R

# gapminder[gapminder$year = 1957,]

gapminder[gapminder$year == 1957,]

- 1列目から4列目以外のすべての列を抽出する

R

# gapminder[,-1:4]

gapminder[,-c(1:4)]

- 寿命が80年以上の行を抽出する

R

# gapminder[gapminder$lifeExp > 80]

gapminder[gapminder$lifeExp > 80,]

- 1行目と4列目、5列目(

continentとlifeExp)を抽出する

R

# gapminder[1, 4, 5]

gapminder[1, c(4, 5)]

- 応用:年 2002 年と 2007 年の情報を含む行を抽出する

R

# gapminder[gapminder$year == 2002 | 2007,]

gapminder[gapminder$year == 2002 | gapminder$year == 2007,]

gapminder[gapminder$year %in% c(2002, 2007),]

Challenge 8

Why does

gapminder[1:20]return an error? How does it differ fromgapminder[1:20, ]?Create a new

data.framecalledgapminder_smallthat only contains rows 1 through 9 and 19 through 23. You can do this in one or two steps.

gapminderis a data.frame so needs to be subsetted on two dimensions.gapminder[1:20, ]subsets the data to give the first 20 rows and all columns.

R

gapminder_small <- gapminder[c(1:9, 19:23),]

- Indexing in R starts at 1, not 0.

- Access individual values by location using

[]. - Access slices of data using

[low:high]. - Access arbitrary sets of data using

[c(...)]. - Use logical operations and logical vectors to access subsets of data.

Content from Control Flow

Last updated on 2025-11-11 | Edit this page

Overview

Questions

- How can I make data-dependent choices in R?

- How can I repeat operations in R?

Objectives

- Write conditional statements with

if...elsestatements andifelse(). - Write and understand

for()loops.

Often when we’re coding we want to control the flow of our actions. This can be done by setting actions to occur only if a condition or a set of conditions are met. Alternatively, we can also set an action to occur a particular number of times.

There are several ways you can control flow in R. For conditional statements, the most commonly used approaches are the constructs:

R

# if

if (condition is true) {

perform action

}

# if ... else

if (condition is true) {

perform action

} else { # that is, if the condition is false,

perform alternative action

}Say, for example, that we want R to print a message if a variable

x has a particular value:

R

x <- 8

if (x >= 10) {

print("x is greater than or equal to 10")

}

x

OUTPUT

[1] 8The print statement does not appear in the console because x is not

greater than 10. To print a different message for numbers less than 10,

we can add an else statement.

R

x <- 8

if (x >= 10) {

print("x is greater than or equal to 10")

} else {

print("x is less than 10")

}

OUTPUT

[1] "x is less than 10"You can also test multiple conditions by using

else if.

R

x <- 8

if (x >= 10) {

print("x is greater than or equal to 10")

} else if (x > 5) {

print("x is greater than 5, but less than 10")

} else {

print("x is less than 5")

}

OUTPUT

[1] "x is greater than 5, but less than 10"Important: when R evaluates the condition inside

if() statements, it is looking for a logical element, i.e.,

TRUE or FALSE. This can cause some headaches

for beginners. For example:

R

x <- 4 == 3

if (x) {

"4 equals 3"

} else {

"4 does not equal 3"

}

OUTPUT

[1] "4 does not equal 3"As we can see, the not equal message was printed because the vector x

is FALSE

R

x <- 4 == 3

x

OUTPUT

[1] FALSEChallenge 1

Use an if() statement to print a suitable message

reporting whether there are any records from 2002 in the

gapminder dataset. Now do the same for 2012.

We will first see a solution to Challenge 1 which does not use the

any() function. We first obtain a logical vector describing

which element of gapminder$year is equal to

2002:

R

gapminder[(gapminder$year == 2002),]

Then, we count the number of rows of the data.frame

gapminder that correspond to the 2002:

R

rows2002_number <- nrow(gapminder[(gapminder$year == 2002),])

The presence of any record for the year 2002 is equivalent to the

request that rows2002_number is one or more:

R

rows2002_number >= 1

Putting all together, we obtain:

R

if(nrow(gapminder[(gapminder$year == 2002),]) >= 1){

print("Record(s) for the year 2002 found.")

}

All this can be done more quickly with any(). The

logical condition can be expressed as:

R

if(any(gapminder$year == 2002)){

print("Record(s) for the year 2002 found.")

}

Did anyone get a warning message like this?

ERROR

Error in if (gapminder$year == 2012) {: the condition has length > 1The if() function only accepts singular (of length 1)

inputs, and therefore returns an error when you use it with a vector.

The if() function will still run, but will only evaluate

the condition in the first element of the vector. Therefore, to use the

if() function, you need to make sure your input is singular

(of length 1).

Tip: Built in ifelse()

function

R accepts both if() and

else if() statements structured as outlined above, but also

statements using R’s built-in ifelse()

function. This function accepts both singular and vector inputs and is

structured as follows:

where the first argument is the condition or a set of conditions to

be met, the second argument is the statement that is evaluated when the

condition is TRUE, and the third statement is the statement

that is evaluated when the condition is FALSE.

R

y <- -3

ifelse(y < 0, "y is a negative number", "y is either positive or zero")

OUTPUT

[1] "y is a negative number"Tip: any() and

all()

The any() function will return TRUE if at

least one TRUE value is found within a vector, otherwise it

will return FALSE. This can be used in a similar way to the

%in% operator. The function all(), as the name

suggests, will only return TRUE if all values in the vector

are TRUE.

Repeating operations

If you want to iterate over a set of values, when the order of

iteration is important, and perform the same operation on each, a

for() loop will do the job. We saw for() loops

in the shell

lessons earlier. This is the most flexible of looping operations,

but therefore also the hardest to use correctly. In general, the advice

of many R users would be to learn about for()

loops, but to avoid using for() loops unless the order of

iteration is important: i.e. the calculation at each iteration depends

on the results of previous iterations. If the order of iteration is not

important, then you should learn about vectorized alternatives, such as

the purrr package, as they pay off in computational

efficiency.

The basic structure of a for() loop is:

For example:

R

for (i in 1:10) {

print(i)

}

OUTPUT

[1] 1

[1] 2

[1] 3

[1] 4

[1] 5

[1] 6

[1] 7

[1] 8

[1] 9

[1] 10The 1:10 bit creates a vector on the fly; you can

iterate over any other vector as well.

We can use a for() loop nested within another

for() loop to iterate over two things at once.

R

for (i in 1:5) {

for (j in c('a', 'b', 'c', 'd', 'e')) {

print(paste(i,j))

}

}

OUTPUT

[1] "1 a"

[1] "1 b"

[1] "1 c"

[1] "1 d"

[1] "1 e"

[1] "2 a"

[1] "2 b"

[1] "2 c"

[1] "2 d"

[1] "2 e"

[1] "3 a"

[1] "3 b"

[1] "3 c"

[1] "3 d"

[1] "3 e"

[1] "4 a"

[1] "4 b"

[1] "4 c"

[1] "4 d"

[1] "4 e"

[1] "5 a"

[1] "5 b"

[1] "5 c"

[1] "5 d"

[1] "5 e"We notice in the output that when the first index (i) is

set to 1, the second index (j) iterates through its full

set of indices. Once the indices of j have been iterated

through, then i is incremented. This process continues

until the last index has been used for each for() loop.

Rather than printing the results, we could write the loop output to a new object.

R

output_vector <- c()

for (i in 1:5) {

for (j in c('a', 'b', 'c', 'd', 'e')) {

temp_output <- paste(i, j)

output_vector <- c(output_vector, temp_output)

}

}

output_vector

OUTPUT

[1] "1 a" "1 b" "1 c" "1 d" "1 e" "2 a" "2 b" "2 c" "2 d" "2 e" "3 a" "3 b"

[13] "3 c" "3 d" "3 e" "4 a" "4 b" "4 c" "4 d" "4 e" "5 a" "5 b" "5 c" "5 d"

[25] "5 e"This approach can be useful, but ‘growing your results’ (building the result object incrementally) is computationally inefficient, so avoid it when you are iterating through a lot of values.

Tip: don’t grow your results

One of the biggest things that trips up novices and experienced R users alike, is building a results object (vector, list, matrix, data frame) as your for loop progresses. Computers are very bad at handling this, so your calculations can very quickly slow to a crawl. It’s much better to define an empty results object before hand of appropriate dimensions, rather than initializing an empty object without dimensions. So if you know the end result will be stored in a matrix like above, create an empty matrix with 5 row and 5 columns, then at each iteration store the results in the appropriate location.

A better way is to define your (empty) output object before filling in the values. For this example, it looks more involved, but is still more efficient.

R

output_matrix <- matrix(nrow = 5, ncol = 5)

j_vector <- c('a', 'b', 'c', 'd', 'e')

for (i in 1:5) {

for (j in 1:5) {

temp_j_value <- j_vector[j]

temp_output <- paste(i, temp_j_value)

output_matrix[i, j] <- temp_output

}

}

output_vector2 <- as.vector(output_matrix)

output_vector2

OUTPUT

[1] "1 a" "2 a" "3 a" "4 a" "5 a" "1 b" "2 b" "3 b" "4 b" "5 b" "1 c" "2 c"

[13] "3 c" "4 c" "5 c" "1 d" "2 d" "3 d" "4 d" "5 d" "1 e" "2 e" "3 e" "4 e"

[25] "5 e"Tip: While loops

Sometimes you will find yourself needing to repeat an operation as

long as a certain condition is met. You can do this with a

while() loop.

R will interpret a condition being met as “TRUE”.

As an example, here’s a while loop that generates random numbers from

a uniform distribution (the runif() function) between 0 and

1 until it gets one that’s less than 0.1.

R

z <- 1

while(z > 0.1){

z <- runif(1)

cat(z, "\n")

}

while() loops will not always be appropriate. You have